Assistant Professor Gary Lyn's research includes international economics and mathematical and quantitative methods. Larger image. Photo by Christopher Gannon/Iowa State University

AMES, IA – When people talk about adapting to climate change, they often refer to innovations – a new crop variety that can withstand more extreme heat or building underwater pumps to cool coral reefs. But Gary Lyn, an assistant professor who specializes in international trade and economic geography at Iowa State University, says trade, migration and job options will also affect how individual states and countries fare over the next 100 years.

Lyn is part of a research team that developed an economic model to better understand these three market adaptations. He co-authored a working paper and presented its findings Oct. 28 at a joint seminar with Washington University St. Louis and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

"Most models don't take into consideration that geographic locations are linked in particular ways through trade and migration and that people may change jobs," said Lyn. "Our model shows that these linkages really matter when trying to think about the economic impacts of climate change, and we shouldn't ignore them."

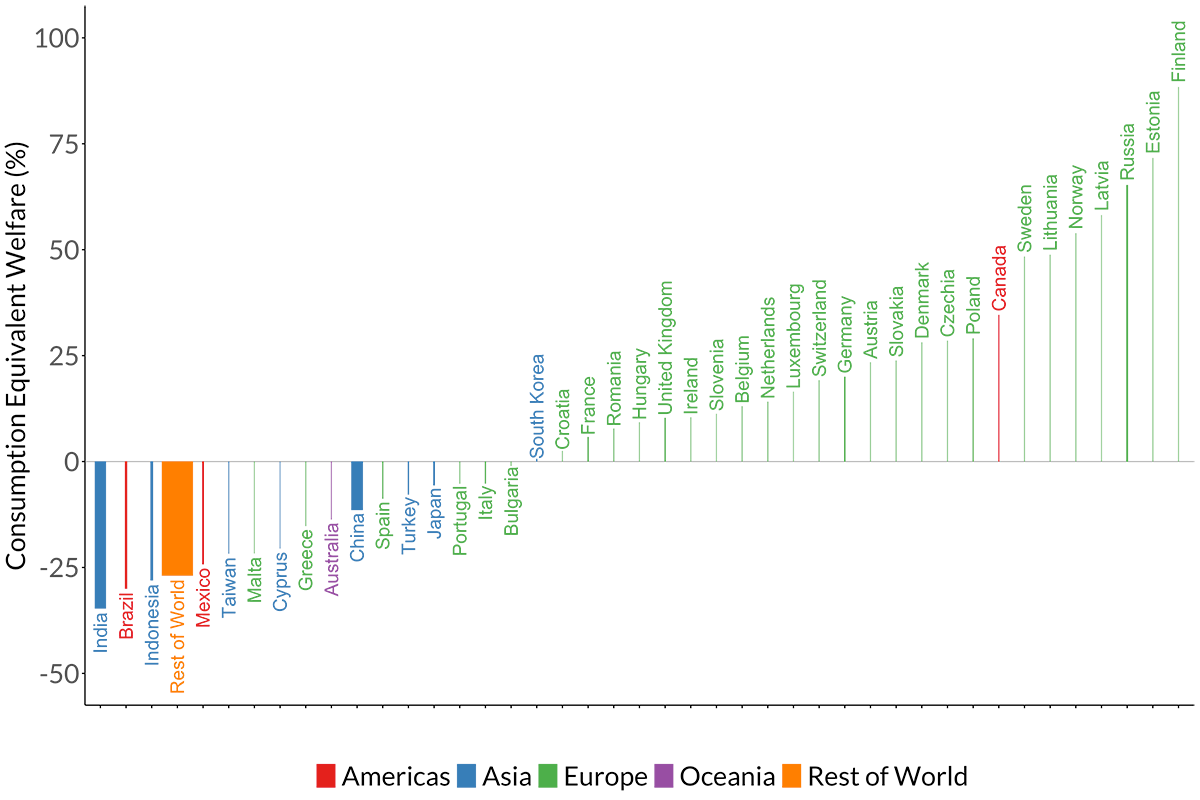

The researchers' model predicts the global economy will take more than a 20% hit by 2100. Countries with colder regions will be better positioned to buffer some of the impacts.

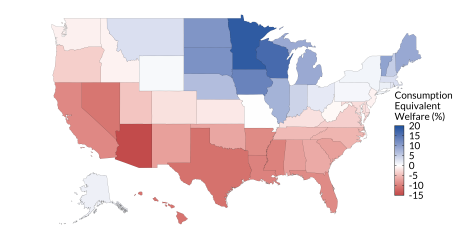

Full economic model simulated for 2015-2100. Larger image.

In the U.S., migration will shift from the south – states like Texas, Arizona and California – to the Upper Midwest and Northeast. Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota are expected to see the largest increases as people seek refuge from higher temperatures.

"Florida is predicted to get unbearably hot in 100 years, but people don't have to stay there. They can move, which is a form of adaptation," said Lyn.

The model also shows the Upper Midwest and Northeast will play a much bigger role in producing goods in the U.S. as jobs, especially in agriculture and manufacturing, shift north. Southern states are expected to experience economic losses with this change and rely more heavily on trade over time.

States with more options for people to change jobs if they work in an industry directly impacted by climate change may be able to slow migration and economic losses.

Lyn says the model indicates trade between states will have a bigger role than migration and job switching in the U.S. economy as it adapts to climate change, but the "combination of all three is greater than the sum of their parts."

The researchers acknowledge their model is working within certain limitations. New innovations or policies in the next 100 years could alter the climate change trajectory or help communities adapt in ways that are impossible to predict now. But by isolating the impacts of certain factors and seeing how they interact, the researchers show trade, migration and job options need to be part of the discussion.

Full model simulation from 2015-2022 estimates economic impacts from climate change by country. Larger image.