In the aftermath of the tidal wave that hit the archipelago, three members of the University community share how tsunamis have impacted their personal and professional lives.

The waiting was the hardest part.

Two days after the deadliest tsunami in recorded history slammed into the coasts of a dozen South and Southeast Asian countries, killing hundreds of thousands of people, Suresh Atapattu still hadn't heard from his mother and father in Sri Lanka.

The small island nation bore the brunt of the destructive wave, which hit a day after Christmas of 2004 and was triggered by a magnitude-9.1 undersea earthquake.

With most communication lines out of the country severed, he feared the worst. "I had to rely on television and internet news coverage for updates," said Atapattu, who was a graduate student at the University of Miami at the time. "What was frightening was that the reports got progressively worse as the scale of the damage sunk in."

Then, he finally got word: His parents, who lived just south of Sri Lanka's largest city, Colombo, were safe.

He would visit his homeland seven months later, seeing firsthand the devastation wrought by the powerful tsunami.

"The cleanup and rebuilding were in progress, but everyone still seemed traumatized by the scale of the disaster," recalled Atapattu, now a biomedical engineer in the Miller School of Medicine's International Medicine Institute. "There were stories of people who happened to be in the path of the waves and simply disappeared. And the randomness of the loss weighed heavily on everyone. Those who lived at a certain elevation escaped tragedy, while neighbors on lower ground lost everything."

In the wake of the tsunami that hit Tonga on Jan. 15 in the South Pacific Ocean, Atapattu couldn't help but think of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that took the lives of so many. At least 35,000 people perished in his homeland.

The Tonga tsunami also rekindled memories for Sanjeev Chatterjee, a professor of cinema and interactive media at the School of Communication, who was in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands immediately after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, filming for his documentary "One Water."

The most compelling memory for Chatterjee: seeing an entire settlement wiped out by water with only the outlines of dwellings on the ground. "In front of many of these remnants were dogs that must have been part of those households. They were crying," he recalled. "Later, I was told that the dogs sought higher ground early and returned once the water had receded."

For Gregor Eberli, the Robert N. Ginsburg Endowed Chair in Marine Geosciences at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, tsunamis are an area of inquiry without limits. Ever since the devastating Boxing Day tsunami 18 years ago, he has been studying their dynamics, researching everything from the sedimentology record of tsunamis in the Indian Ocean to the likelihood of a tsunami hitting South Florida.

"A colleague (professor of marine geosciences Falk Amelung) and a student(Kelly Jackson) of mine went to Sri Lanka to the devastated coast and took cores from coastal lagoons to search for earlier tsunami deposits," Eberli noted. "One lagoon proved to have an excellent record of older tsunami deposits and allowed us to establish the recurrence rate of such devastating tsunamis in the Indian Ocean."

But it is Eberli's research on the possibility of a tsunami strike on South Florida that garnered a significant amount of attention six years ago.

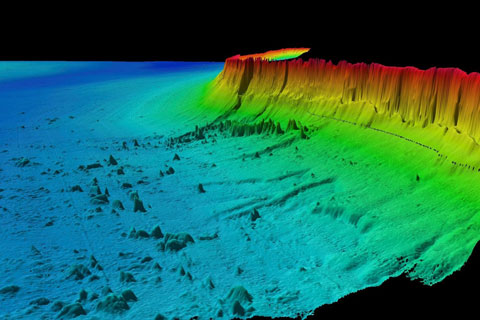

While it is possible for a tsunami to hit South Florida, the probability of such an occurrence is low, he said. "The origin of tsunamis in South Florida would be from large submarine landslides that displace large portions of water," he explained. "The size of the tsunami is directly proportional to the volume of the displaced water. Such submarine landslides are triggered by several processes, where there's high seismicity from powerful earthquakes. Luckily, there are very few earthquakes in the Florida-Bahamas region."

The last three, he said, occurred along a fault system north of Cuba in early 2015, and none was strong enough to trigger submarine landslides. The last reported tsunami was in the 1950s when a small earthquake-triggered tsunami invaded Havana Harbor.

For the 2016 study, on which he served as a senior author, Eberli and his group used numerical models to construct tsunamis generated by submarine landslides along the western Great Bahama Bank (GBB), with Florida as an impact point. They also modeled tsunamis generated by a margin collapse in the southeastern GBB, with northern Cuba as main impact area. Additionally, they used sediment parameters along GBB to investigate the potential for future landslides.

The researchers found that certain submarine landslides can cause smaller waves capable of generating dangerous currents along the Florida coast but none of them powerful enough to create treacherous tsunami waves. In a worst-case scenario, however, they discovered that larger and faster landslides would create waves of 4.5 meters and 9.5 meters for the east coast of Florida and northern Cuba, respectively.

Eberli has also investigated the potential of a tsunami impacting a Florida nuclear power plant. "This was, of course, a concern as a fault movement triggered the devastating tsunami that hit the nuclear power plant in Japan in 2011," Eberli said. "However, Japan is next to a subduction zone where large displacement along faults can occur. This is not the case in the Florida-Bahamas region, and thus, the risk of a tsunami from neotectonics [recent deformations of the Earth's crust] is basically nil."

Eberli said regions of the world where tsunamis occur most often are located close to subduction zones, which are also areas of heavy volcanic activity.

"But the subduction zone produces the most devastating tsunamis," he explained. "In the subducting plate, stress builds up that gets released catastrophically. These sudden releases move large portions of the plate that displace the water. The Sumatra-Andaman earthquake of 2004 ruptured the seafloor over 1,000 kilometers, producing a mega-tsunami."

He explained that the damage from tsunamis is related to the run-up distance of the water from the wave. Flat-lying areas become inundated over larger distances, experiencing much greater devastation than sloping coastlines. And low-lying atolls, he pointed out, are especially prone to being washed away by tsunami waves.