A couple in West Yorkshire, England, are hoping that a scientist at the Medical University of South Carolina and his team are on track to find a treatment for the rare genetic disorder their son suffers from: MEF2C Haploinsufficiency Syndrome, also known as MHS and MCHS.

Lorena Garcia Fernandez and her husband, James Kelly, hadn't heard of it when Elijah was born in February of 2020. But they sensed something was off, Kelly said. "At about four months, we could tell this didn't feel normal.The eye contact's not really there. The rolling over was delayed. Some of these milestones were very delayed. We're like, this feels a bit odd."

So they asked a pediatrician about Elijah's progress. "They said, 'Ah, he'll be fine. He'll catch up, don't worry about it.'" And then at about eight months, he had his first seizure. That triggered the whole cascade of events," Kelly said.

The quest for a diagnosis

Elijah was hospitalized while doctors tried to figure out what was wrong. "He had a battery of tests like MRIs, spinal taps, EEGs, blood tests, but couldn't find the problem. So the neurologist felt the explanation had to be genetic," Kelly said.

It was. Elijah's mother remembers getting the results of genetic testing that pointed to MEF2C Haploinsufficiency Syndrome "We had no idea what this was. I had to Google it," she said.

MEF2C Haploinsufficiency Syndrome refers to a mutation in the MEF2C gene that can cause "significant cognitive and physical impairments," according to the MEF2C Foundation.

"Individuals often experience severe to profound developmental delay, low muscle tone (hypotonia), seizures, stereotypic movements and subtle characteristic facial features," its website says.

But back at the time of Elijah's diagnosis, his parents knew none of that. "We were like, 'What is MEF2C?'" Kelly said. "So you stick that into Google and up comes a load of literature, and so you start combing through that. And one common thread was Chris' name."

Connecting with Cowan

Chris is Christopher Cowan, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Neuroscience at the Medical University of South Carolina. He's a leading researcher on MEF2C, a professor, the director of the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence in Neurodevelopment and Its Disorders and the SmartState Endowed Chair in Brain Imaging at MUSC.

"This all began as a basic science question more than 20 years ago. I was interested in understanding how the brain decides which synaptic connections that are formed during brain development are kept and which ones are eliminated," Cowan said.

"And this is a natural process that happens in our brain and actually continues to happen until about 18 years of age for most of us. And that synaptic remodeling or refinement is part of how our brain circuitry is established and how it adapts to our experiences."

In 2006, Cowan and his colleagues published an article in the journal Science about how "neurons impact the strength and number of synapses formed." Cowan was at Harvard Medical School at the time.

"The genetic program that coordinates this process is poorly understood," the scientists wrote. "We show that myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) transcription factors suppressed excitatory synapse number in a neuronal activity- and calcineurin-dependent manner as hippocampal neurons formed synapses."

Translation: They were getting closer to understanding a key factor in brain development. Other scientists were on the hunt, too.

Discovery of MEF2C gene

Following the earlier discovery of the MEF2C gene by Stuart Lipton, M.D., Ph.D., now at Scripps Research, a clinical report about several patients with mutations in MEF2C came out.

"These patients presented with a severe neurodevelopmental disorder, including a high number of patients with seizures, intellectual disability, autism symptoms, motor-related problems and a number of other features," Cowan said.

It was an "aha" moment for the neuroscientist. "I started getting a clue at that point that this particular MEF2 gene was probably super important. I decided to shift my focus to try to understand how MEF2C shapes brain development because it had clear relevance to human nervous system development and function."

His team found that when one of the two copies of the MEF2C gene in the brain is deleted or mutated, it triggers major changes."It turns out this MEF2C gene is a transcription factor, which means it's a protein that affects the expression of many, many other genes. Hundreds, thousands, probably." Gene expression refers to the way genes turn their encoded information into action.

Families and scientists have meeting of minds

While that work was underway, Elijah's parents were busy trying to find a treatment for their son, Kelly said. "So we reached out to Chris and started having conversations, and I managed to get a face-to-face meeting with Chris in October of 2022."

Elijah was then 2 years old. Kelly and his wife didn't want to waste a second. "Chris and I sat down and started talking about opportunities to put a proposal together for developing treatments for MEF2C. Because most of everybody's work in this field has been focused on mechanistic studies." Mechanistic studies involve examining how factors like MEF2C work in cells and organs to influence normal brain and body function.

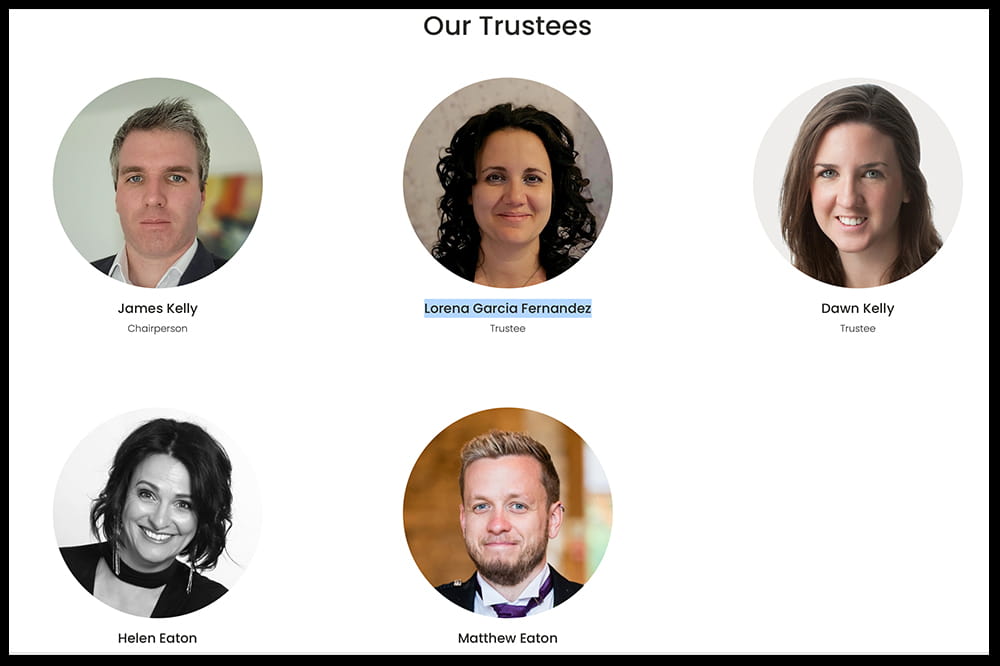

Kelly and his family, including his sister, Dawn Kelly, along with Helen and Matthew Eaton, parents of Lyra who also has MCHS, started the MEF2C Foundation. The idea was to bring together people dealing with a disorder that so far has no treatment and fund the work of scientists trying to change that.

"There are a few different routes that we could have gone down, but Chris's recommendation was always, 'We need to go after the root cause.' There are limitations to trying to find drugs to treat the specific end points of the disease, like the epilepsy or the hypotonia or the social deficits or whatever. Because you'll be there all day. You might need many different drugs to treat individual symptoms," Kelly said.

"So the focus of his proposal has been on how to increase the amount of this MEF2C protein in the brain, which is where we need it the most."

Cowan's team strategizes

Cowan said he and Alain Grieg, one of his graduate students, started thinking about a couple of different strategies. "And I had another student, Jennifer Cho, in the lab, and a postdoc, Adam Harrington, who were working on a viral-mediated approach to try to treat MCHS. And then Alain and I were trying to think of ways to use an RNA-based therapeutic approach. And so we approached James, Helen and the other board members and said, 'Well, here are some ideas.'"

One was a gene therapy approach. The others were what Kelly called micro-RNA therapeutics. "any of these approaches could help increase the amount of the MEF2C protein in the cells of the brain, but we decided to advance one of the RNA-based approaches since it offered several advantages and looked very promising," Kelly said.

The MEF2C Foundation recently announced that it has committed half a million dollars over two years to fund Cowan's therapeutic research. This was made possible through a huge fundraising campaign by the MEF2C community and with contributions from other international MEF2C organizations.

"I was very clear with them. We had no idea if any of these potential treatments are going to work. But we've been really encouraged by our initial six months of effort into this. We've already found multiple RNA-based therapeutics that appear to be increasing MEF2C levels. So we're hopeful that we can move this forward quickly," Cowan said.

Kelly is, too. "I'm hoping through 2024, we're gonna get some really compelling data from the ongoing experiments and tests that start to prove that this method is actually effective at rescuing the symptoms," he said, referring to the RNA therapeutics.

"I haven't really thought much beyond that. I mean, if that happens, that's really groundbreaking. If we can prove that MCHS symptoms are reversible or rescuable, that's a game changer."

It's new territory for Cowan's lab, which has typically focused on fundamental science, not treatments. He's thrilled by the idea of what the future may hold. "I've spent the last 30 years of my life working in neuroscience. To have the possibility of having an impact on patients is kind of a dream come true."