An unmistakable takeaway from sessions of "UnrulyArt" is that all those "-n'ts" - can't, needn't, shouldn't, won't - which can lead people to exclude children with disabilities or cognitive, social, and behavioral impairments from creative activities, aren't really rules. They are merely assumptions and stigmas.

When a session ends and the paint that was once flying is now just drying, the rewards that emerge are more than the individual works the children and their volunteer helpers created. There is also the joy and the intellectual engagement that maybe was experienced differently but nevertheless could be shared equally between the children and the volunteers.

When MIT professor Pawan Sinha first launched UnrulyArt in 2012, his motivation was to share the joy and fulfillment he personally found in art with children in India who had just gained their sense of sight through a program he founded called Project Prakash.

"I felt that this is an activity that may also be fun for children who have not had an opportunity to engage in art," says Sinha, professor of vision and computational neuroscience in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences (BCS). "Children with disabilities are especially deprived in this context. Societal attitudes toward art can keep it away from children who suffer from different kinds of cognitive, sensory, or motoric challenges."

Margaret Kjelgaard, an assistant professor at Bridgewater State University and Sinha's longtime colleague in autism research and in convening UnrulyArt sessions, says that the point of the art is the experience of creation, not demonstrations of skill.

"It's not about fine art and being precise," says Kjelgaard, whose autistic son had a blast participating in his own UnrulyArt session a decade ago and still enjoys art. "It's about just creating beautiful things without constraint."

UnrulyArt's ability to edify both children with developmental disabilities and the scientists who study their conditions interleaves closely with the mission of the Simons Center for the Social Brain (SCSB), says Director Mriganka Sur. That's why SCSB sponsored and helped to staff four sessions of UnrulyArt recently in Belmont and Burlington, Massachusetts.

"As an academic research center, SCSB activities focus mainly on science and scientists," says Sur, the Newton Professor in BCS and The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT. "Our team thought this would be a wonderful opportunity for us to do something outside the box."

Getting unruly

At a session in a small event hall in Burlington, SCSB postdocs and administrators and members of Sinha's lab laid down tarps and set up stations of materials for dozens of elementary school children from the LABBB Educational Collaborative, which provides special education services to schoolchildren from ages 3 through 22 from local communities. In all, UnrulyArt hosted approximately 60 children across four sessions earlier this spring, says program director Donna Goodell.

Previous item Next item

"It's also a wonderful social opportunity as we bring different cohorts of students together to participate," she notes.

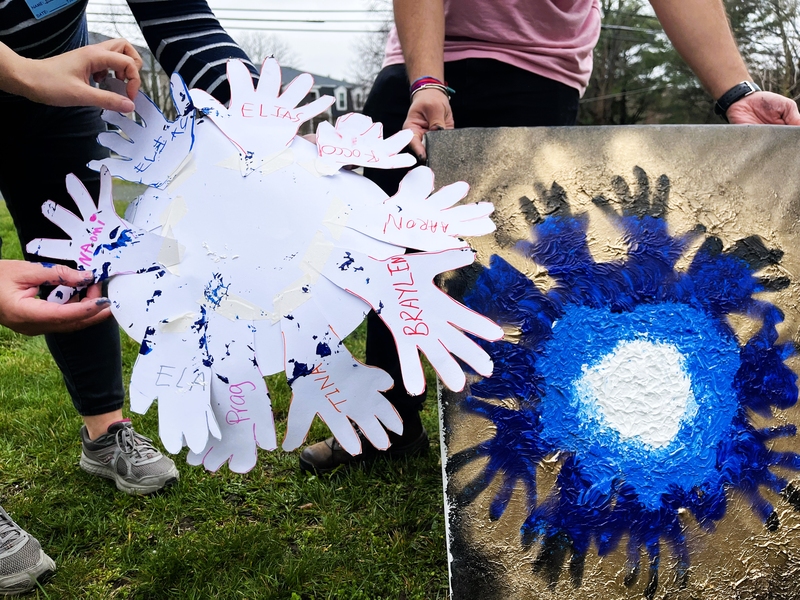

With the room set up, kids came right in to get unruly with the facilitation of volunteers. Some children painted on sheets of paper at tables, as any other children would. Other children opted to skate around on globs of paint on a huge piece of paper on the floor. Many others, including some in wheelchairs who struggled to hold a brush, were aided by materials and techniques cleverly conceived to enable aesthetic results.

For instance, children of all abilities could drop dollops of paint on paper that, when folded over, created a symmetric design. Others freely slathered paints on boards that had been pre-masked with tape so that when the tape was removed, the final image took on the hidden structure. Yet others did the same with smaller boards where removal of a heart-shaped mask revealed a heart of a different color.

One youngster sitting on the floor with Sinha Lab graduate student Charlie Shvartsman was elated to learn that he was free to drop paint on paper and then slap it hard with his hands.

Previous item Next item

Researcher reflections

The volunteers worked hard, not only setting up and facilitating but also drying paintings and cleaning up after each session. Several of them expressed a deep sense of personal and intellectual reward from the experience.

"I paint as a hobby and wanted to experience how children on the autism spectrum react to the media, which I find very relaxing," says Chhavi Sood, a Simons Fellow in the lab of Menicon Professor Troy Littleton in BCS, the Department of Biology, and The Picower Institute.

Sood works with fruit flies to study the molecular mechanisms by which mutation in an autism-associated gene affects neural circuit connections.

"[UnrulyArt] puts a human face to the condition and makes me appreciate the diversity of the autism spectrum," she says. "My work is far from behavioral studies. This experience broadened my understanding of how autism spectrum disorder can manifest differently in people."

Simons Fellow Tomoe Ishikawa, who works in the lab of BCS and Picower Institute Associate Professor Gloria Choi, says she, too, benefited from the chance to observe the children's behavior as she helped them. She said she saw exciting moments of creativity, but also notable moments where self-control seemed challenging. As she is studying social behavior using mouse models in the lab, she says UnrulyArt helped increase her motivation to discover new therapies that could help autistic children with behavioral challenges.

Previous item Next item

Suayb Arslan, a visiting scholar in Sinha's Lab who studies human visual perception, saw many connections between his work and what unfolded at UnrulyArt. This was visual art, after all, but then there was the importance of creativity in many facets of life, including doing research. And Arslan also valued the chance to work with children with different challenges to see how they processed what they were seeing.

He anticipated that the experience would be so valuable that he came with his wife Beyza and his daughter Reyyan, who made several creations alongside the other kids. Reyyan, he says, is enrolled in a preschool program in Cambridge that by design includes typically developing children like her with kids with various challenges and differences.

"I think that it's important that she be around these kids to sit down together with them and enjoy the time with them, have fun with them and with the colors," Arslan says.