The United States government has apparently failed to provide compensation or other redress to Iraqis who suffered torture and other abuse two decades after evidence emerged of US forces mistreating detainees at Abu Ghraib and other US-run prisons in Iraq, Human Rights Watch said today.

After the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, the US and its coalition allies held about 100,000 Iraqis between 2003 and 2009. Human Rights Watch and others have documented torture and other ill-treatment by US forces in Iraq. Survivors of abuse have come forward for years to give their accounts of their treatment, but received little recognition from the US government and no redress. Prohibitions against torture under US domestic law, the Geneva Conventions of 1949, and the United Nations Convention Against Torture, as well as customary international law, are absolute.

"Twenty years on, Iraqis who were tortured by US personnel still have no clear path for filing a claim or receiving any kind of redress or recognition from the US government," said Sarah Yager, Washington director at Human Rights Watch. "US officials have indicated that they prefer to leave torture in the past, but the long-term effects of torture are still a daily reality for many Iraqis and their families."

Between April and July 2023, Human Rights Watch interviewed Taleb al-Majli, a former detainee at Abu Ghraib prison, in addition to three people with knowledge of his detention and his condition after his release who wished to remain anonymous. Human Rights Watch also interviewed a former US judge advocate who served in Baghdad in 2003, a former member of Iraq's High Commission for Human Rights, and representatives of three nongovernmental organizations working on torture. Human Rights Watch also reviewed media and nongovernmental reports, as well as US government documents including US Department of Defense investigations into alleged detainee abuse.

In May, Al-Majli told Human Rights Watch that US forces subjected him to torture and other ill-treatment, including physical, psychological, and sexual humiliation while detaining him at Abu Ghraib prison between November 2003 and March 2005.

He said he was one of the men in a widely circulated photo at Abu Ghraib that shows a group of naked, hooded prisoners on top of one another in a human pyramid, while two US soldiers smile behind them. "Two American soldiers, one male and one female, ordered us to strip naked," al-Majli said. "They piled us prisoners on top of each other. I was one of them."

Al-Majli said that US forces detained him while he was visiting relatives in Anbar province in 2003.

"On the morning of October 31 [2003], US forces surrounded the village my uncle lived in," al-Majli said. "They took boys and old men from the village. I told them I'm a guest from Baghdad, I live in Baghdad and just came to visit my uncle. They put a cover on my head and tied my wrists with plastic zip ties, then loaded me into a Humvee."

After a few days at Habbaniya military base and at an unknown location in Iraq, US forces moved al-Majli to Abu Ghraib prison. "It was then the torture started," he said. "They took away our clothes. They mocked us constantly while we were blindfolded with hoods over our heads. We were completely powerless," he said. "I was tortured by police dogs, sound bombs, live fire, and water hoses."

While Human Rights Watch is unable to conclusively verify al-Majli's account, including whether he was one of the men in the "human pyramid" photo, his story of detention at Abu Ghraib is credible. Al Majli presented corroborating evidence, including a prisoner identity card with his full name, inmate number, and cell block, which he said US forces issued him at Abu Ghraib after taking his photo, iris scan, and fingerprints. Al-Majli also showed Human Rights Watch a letter he obtained in 2013 from the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights, a governmental body with the mandate to protect and promote human rights in Iraq, confirming his detention at Abu Ghraib prison, including his date of arrest (October 31, 2003), and listing the same inmate number as his prisoner identity card.

He said he has kept them all this time as proof of what he endured.

During the US occupation of Iraq from 2003 to 2011, authorities held thousands of men, women, and children at Abu Ghraib prison. A February 2004 report to the US-led military coalition by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), said that military intelligence officers told the ICRC that an estimated 70 to 90 percent of people in coalition custody in Iraq in 2003 had been arrested by mistake.

Al-Majli said that after 16 months at Abu Ghraib, he was released without charge. Though he gained his freedom, he said he found himself physically ailing, penniless, and traumatized. While he was detained, he said, he began biting his hands and wrists to cope with the trauma he was experiencing, and has continued ever since. Raised, purple welts were clearly visible across his hands and wrists.

"It became a mental health condition," he said. "I did it in jail, and after I left jail, and I keep doing it today. I try to avoid it, but I can't. Until today, I can't wear short sleeves. When people see this, I tell them it's burns. I avoid questions."

More than the pain he suffered himself, al-Majli laments the negative effect it has had on his children: "This one year and four months changed my entire being for the worse. It destroyed me and destroyed my family. It's the reason for my son's health problems and the reasons my daughters dropped out of school. They stole our future from us."

For two decades, al-Majli has sought redress, including compensation and an apology, for the abuse he suffered. Unable to afford a lawyer or access the US embassy in Baghdad, al-Majli sought help from the Iraqi Bar Association, which turned him away, telling him it did not handle cases like his. Al-Majli then went to the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights, but all it could do was issue him a letter confirming he is in their records as a former detainee at Abu Ghraib. He said he did not know how to contact the US military and raise a claim.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the US Department of Defense on June 6, 2023, outlining al-Majli's case, providing the research findings, and requesting information on compensation for survivors of torture in Iraq. Despite repeated follow-up requests, Human Rights Watch has not received a response.

"I didn't know what else I could do or where else to go," al-Majli said. Human Rights Watch was not able to find any legal pathway for al-Majli to file a claim seeking recompense.

"The US secretary of defense and attorney general should investigate allegations of torture and other abuse of people detained by the US abroad during counterinsurgency operations linked to its 'Global War on Terrorism'," Yager said. "US authorities should initiate appropriate prosecutions against anyone implicated, whatever their rank or position. The US should provide compensation, recognition, and official apologies to survivors of abuse and their families."

20 Years of US Silence

In 2004, then-US President George W. Bush apologized for the "humiliation suffered by the Iraqi prisoners" at Abu Ghraib. Soon after, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld told Congress that he had found a legal way to compensate Iraqi detainees who suffered "grievous and brutal abuse cruelty at the hands of a few members of the United States armed forces. It's the right thing to do, and it is my intention to see that we do."

Human Rights Watch has found no evidence that the US government has paid any compensation or other redress to victims of detainee abuse in Iraq, nor has the United States issued any individual apologies or other amends.

Twenty years on, Iraqis who were tortured by US personnel still have no clear path for filing a claim or receiving any kind of redress or recognition from the US government. US officials have indicated that they prefer to leave torture in the past, but the long-term effects of torture are still a daily reality for many Iraqis and their families.

Some victims have attempted to apply for compensation using the US Foreign Claims Act (FCA). The law allows foreign nationals to obtain compensation for death, injury, and damage to property from "noncombat activity or a negligent or wrongful act or omission" caused by US service members. However, it includes a so-called combat exclusion: claims are not payable if the harm results from "action by enemy or U.S. forces engaged in armed conflict or in immediate preparation for impending armed conflict." Furthermore, for al-Majli and other survivors of detainee abuse during the invasion and occupation, filing a claim under the Foreign Claims Act is not an option because claims must be filed within two years from the date of the alleged harm.

Human Rights Watch was unable to find public evidence that payments have been made under this law as compensation for detainee abuse, including torture. In 2007, the American Civil Liberties Union obtained documents detailing 506 claims made under the Foreign Claims Act: 488 in Iraq and 18 in Afghanistan. The majority of claims relate to harm or deaths caused by shootings, convoys, and vehicle accidents.

The only case of a Foreign Claims Act payment relating to detention in those documents was for a claimant who was paid US$1,000 for being unlawfully detained in Iraq, with no mention of other abuse. Five other claims were for abuse in detention, but they are among eleven claims that do not contain the outcome, including whether payment was made.

The US Defense Department did not respond to repeated requests for information as to whether the US government made Foreign Claims Act or other compensation payments to survivors or families of those who died of detainee abuse in Iraq.

Jonathan Tracy, a former judge advocate who handled claims of harm in Baghdad in 2003, told Human Rights Watch he did not know of any Foreign Claims Act payments to torture survivors by the Army. "If any of the survivors received a payment, I would doubt the Army would have wanted to use Foreign Claims Act money because it could be interpreted as an admission on the government's part," he said.

A US submission to the UN Committee Against Torture from May 2006 reported that 33 detainees had by that date filed claims for compensation to the US Army, 28 of which were from Iraq.

The submission stated that "no compensation has been provided to date, however, compensation has been offered in two cases." Subsequent submissions to the Committee Against Torture do not contain updates to these figures, nor specify whether those payments were made. Notably, according to the document, neither of the two recommended payments was listed as compensation for torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

Other Iraqis have attempted to find justice in US courts. But the US Justice Department has repeatedly dismissed such cases using a 1946 law that preserves US forces' immunity for "any claim arising out of the combatant activities of the military or naval forces, or the Coast Guard, during time of war."

So far, the only lawsuits able to advance have targeted military contractors. Those cases, too, face considerable obstacles. One such case, Al Shimari et al. v. CACI, has been slowly making its way through courts since June 2008. The lawsuit was brought by the Center for Constitutional Rights, a US-based nongovernmental organization, on behalf of four Iraqi torture victims against CACI International Inc. and CACI Premier Technology, Inc. The lawsuit asserts that CACI, which the US government hired to interrogate prisoners in Iraq, directed and participated in torture and other abuse at Abu Ghraib.

CACI has attempted to have the case dismissed 18 times since it was first filed. On July 31, 2023, a federal judge refused CACI's most recent motion to dismiss the case, which finally appears to be heading to trial.

Criminal Investigations into Detainee Abuse in Iraq

The US Army Criminal Investigation Division (CID) opened at least 506 investigations into alleged abuses of people in the hands of US and other coalition forces in Iraq between 2003 and 2005, according to a US Department of Defense document reviewed by Human Rights Watch. The document details investigations into 376 cases of assault, 90 cases of deaths, 34 cases of theft, and 6 cases of sexual assault allegedly committed by US and coalition forces.

These US Army criminal investigations paint a stark picture of the scale and range of abuse that was alleged inside US-controlled prisons in Iraq. The most high-profile cases - like the killing of Manadel al-Jamadi - and hundreds more cases of abuse that never made headlines are outlined with clinical descriptions of violence.

The investigations concerned 225 allegations of assault and sexual assault in US-controlled detention facilities, involving at least 318 potential victims and 426 alleged abusers.

38 of those investigations upheld the allegations or found the accused guilty.

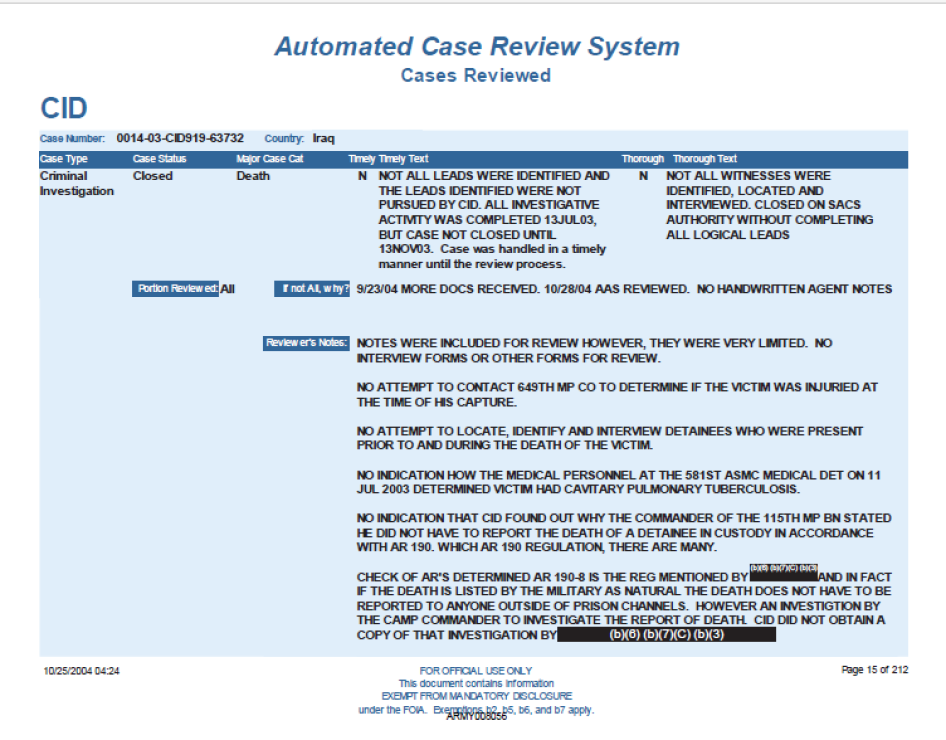

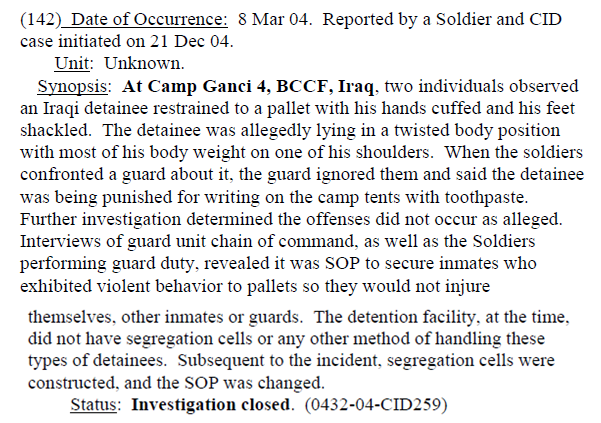

In 57 cases, investigators were unable to find sufficient evidence to prove or disprove the allegation or were unable to identify the suspect. In 79 cases, investigators declared the allegations unfounded. However, cases reviewed by CID highlighted several shortcomings in investigative processes, including a failure to identify and follow leads, failure to locate and interview witnesses, over-reliance on medical records without corroborating evidence, and failure to photograph or examine crime scenes. For example:

In cases in which Army officials interviewed the victims and knew their identities, it appears that no attempt was made to couple punishments of abusers with compensation or other forms of redress.

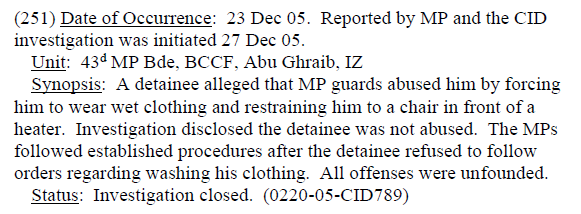

Nineteen allegations of abuse were written off as standard operating procedure, leading the CID to conclude that the "offenses were unfounded" or "did not occur as alleged":

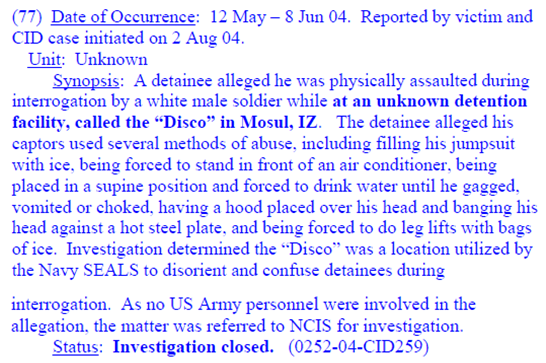

Finally, 16 cases involved allegations of abuse committed by forces other than the US Army. Such cases were referred to investigators of the alleged abuser's branch of the military, such as the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), for further investigation. For example:

A Climate Enabling Torture

When the photos of detainee abuse in Abu Ghraib went public, then-President Bush sought to minimize the systemic nature of the problem by calling it "disgraceful conduct by a few American troops who dishonored our country and disregarded our values." But investigations including by Human Rights Watch have found that decisions taken at the highest levels of government enabled, sanctioned, and justified these acts. Abu Ghraib was but one of several US military detention centers and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) "black sites" worldwide where US forces, intelligence agents, and contractors carried out torture and other ill-treatment, or so-called enhanced interrogation techniques.

When the first detainees arrived at the US Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, from Afghanistan in January 2002, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld labeled them "unlawful combatants," seeking to deny them protections under the Geneva Conventions. The same month, the Bush administration intensified its efforts to circumvent domestic and international prohibitions on torture, with the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel issuing memos that sought to legally justify torture and protect those engaging in it.

Denying detainees these protections enabled Rumsfeld to expand the list of interrogation techniques for use against prisoners at Guantanamo between December 2002 and April 2003.

Subsequent US government investigations, including the 2004 Final Report of the Independent Panel to Review Department of Defense Detention Operations (also known as the Schlesinger report), found that "the augmented techniques [approved by Rumsfeld] for Guantanamo migrated to Afghanistan and Iraq where they were neither limited nor safeguarded."

The use of these techniques violated the prohibition on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of prisoners under the laws of armed conflict and international criminal law.

The Bush administration limited the scope of these policies and practices in subsequent years, including by reducing the list of "enhanced interrogation techniques," but stopped short of banning torture. In January 2009, then-President Barack Obama rescinded all Bush-era memos allowing torture. However, he stated that his administration would prosecute neither the authors of the memos nor those who carried out the acts described in them in the belief that they were legal.

The Legacy of Abu Ghraib

Ninety-seven US soldiers implicated in 38 cases of abuse that the US Army Criminal Investigation Division investigated in Iraqi detention centers between 2003 and 2005 received punishments.

Just 11 of these soldiers were referred to a court martial to face criminal charges, where they were found guilty of crimes including dereliction of duty, maltreatment, aggravated assault, and battery. 9 of the 11 served prison sentences. Fourteen others received nonjudicial punishments (e.g., a fine, reduction in rank, letter of reprimand, or discharge from the service). Reports of disciplinary action were pending for 72 individuals as of the document's publication date, January 13, 2006.

There is no public evidence that any US military officer has been held accountable for criminal acts committed by subordinates under the doctrine of command responsibility.

Human Rights Watch reports in 2005 and 2011 presented evidence warranting substantial criminal investigations into high-level government officials for the roles they played in setting interrogation and detention policies following the September 11, 2001 attacks, including former President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld (now deceased), and CIA Director George Tenet. Additional Human Rights Watch research outlined the systematic nature of torture in Iraq, and the high level of command at which it was condoned.

Every US administration from George W. Bush to Joe Biden has rebuffed efforts for meaningful accountability for torture.

Some steps have been taken to change policies and introduce stricter controls on the treatment of people in US custody abroad. Congress passed new laws, including the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005, which prohibits subjecting anyone in US custody or control, "regardless of nationality or physical location," to "cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment," as defined by the Senate reservation to Article 16 of the Convention Against Torture. The Defense Department also established various offices and positions related to "Detainee Affairs," and initiated a department-wide review of detainee-related policy directives.

In August 2022, the Pentagon released a 36-page action plan aimed at reducing risks to civilians in US military operations. The plan directs the Defense Department to incorporate civilian harm issues into its strategy, planning, training, and doctrine; improve and standardize investigations of civilian harm; and to review and update guidance on responding to civilian harm. However, the plan fails to include a mechanism for reviewing past instances of civilian harm that have gone unaddressed, uninvestigated, and unacknowledged for 20 years.