An entirely new toxic compound found in an Australian tropical sea anemone is being analysed as a potential drug therapy, after it was discovered by QUT biomolecular scientists during investigation of the species' multiple venoms.

- Never-seen-before toxin from tropical sea anemone under analysis

- 84 potential toxins located in tentacles, gut and body of reef-based sea anemone

- Stings cause humans extreme pain but could hold key to new chronic pain-relieving drugs.

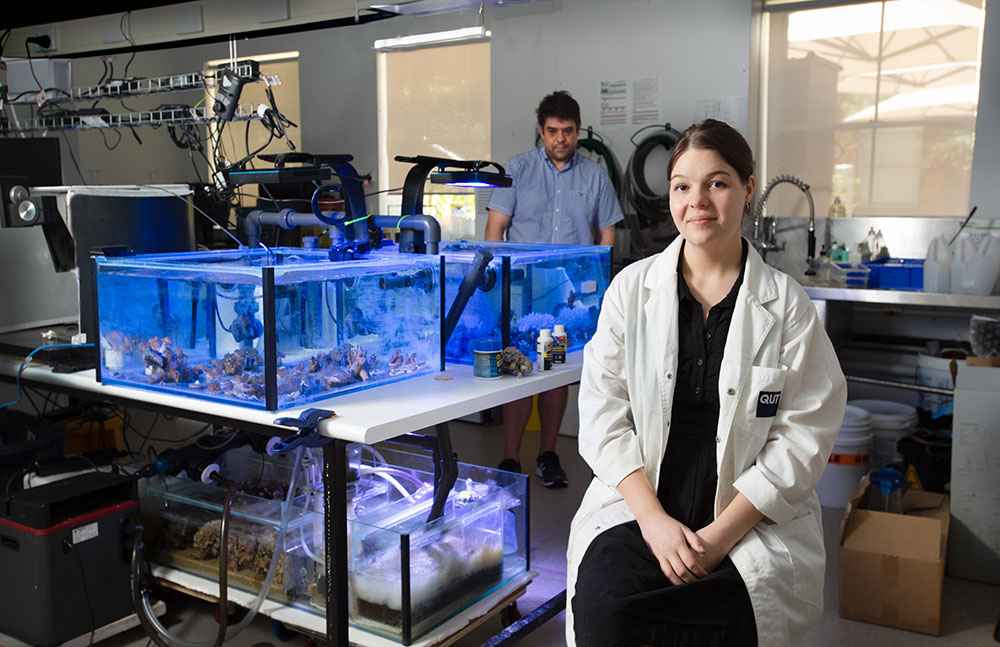

QUT PhD researcher Lauren Ashwood has studied sea anemones' venom makeup extensively, in particular, Telmatactis stephensoni, a reef-based sea anemone that can grow up to 10 cm in diameter.

Ms Ashwood found that this species produced different venoms for biological functions – defence, predation, and digestion – and that the toxins were located at sites that corresponded to their function.

"Unlike snakes which deliver their venom via fangs, T. stephensoni venom is a complex cocktail of toxins that is found in stinging cells throughout the sea anemone's structure," Ms Ashwood said.

"Analysis of the sea anemone's three major functional regions: the tentacles, epidermis and gastrodermis – found the locations of toxin production are consistent with their ecological role of catching prey, defence and digestion.

"This means when we study the toxins in the context of what they do, we have an idea of how they might be useful for therapeutics."

Ms Ashwood said animal venoms had been used to treat humans throughout history, with snake venom administered medicinally as early as the seventh century BC.

"Peptide toxins from venomous animals are being developed into therapeutics for conditions, including cardiovascular disorders, autoimmune diseases, diabetes, wound healing, HIV, cancer and chronic pain," Ms Ashwood said.

"In all, we found 84 potential toxins in T. stephensoni including one that hadn't been seen before. A sample of this unknown toxin, named U-Tstx-1, has been sent to a specialised lab in Hungary for analysis.

"Given that this toxin was found in the gastrodermis of the sea anemone it could be involved in digestion – it could be a new type of co-lipase, enzymes that break down fat.

"This toxin could also be similar to a toxin in the venom of black mamba snakes that stimulates intestinal muscle contractions."

Co-researcher QUT Associate Professor Peter Prentis, from the Centre for Agriculture and the Bioeconomy and the School of Biology and Environmental Science, said scientists were interested in pain-causing venoms because they could potentially be developed to provide pain relief.

"If we can isolate the neurotoxin and find the nerve cell receptor it activates, we could potentially develop a blocker to stop activation and treat conditions such as chronic back pain," Professor Prentis said.

"This means the toxins in the acontia – long, stinging thread used to ward off would-be predators that cause intense pain to marine animals as well as humans – could be a source of an 'antidote' to some types of chronic pain."

Professor Prentis said new analytical techniques had led to a shift towards toxin-driven discovery, away from the earlier method where crude venom was first tested against a target for desired activity.

"This new strategy allows for the discovery of peptides that might have remained undiscovered, for example, those which may not be highly abundant in the venom or which possess unanticipated mechanisms of action," he said.

"Toxin-driven discovery to find therapeutic candidates, however, can be like finding a needle in a haystack and not all peptide toxins are likely to have the same success as pharmaceuticals."

The study, Venoms for all occasions: the functional toxin profiles of different anatomical regions in sea anemones are related to their ecological function was published in Molecular Ecology.