"We have dashboards in place with a number of different datasets," says Lifelile Moakhi - an economist with the office of the Prime Minister of Lesotho - brimming with energy in her office in capital Maseru.

On Wednesday (31 May) the Government of the landlocked kingdom of around 2 million people in southern Africa launched a GIS (geospatial information systems) platform, facilitated by the World Food Programme (WFP) that could be a game-changer for the country on a number of fronts, not least in training and providing resources for up to 3,000 farmers to anticipate, and prepare for, extreme weather events.

"Climate change is affecting us as it does any other country - abnormal seasons, rainy when it's not supposed to be, dry winters… it affects our cropping," says Moakhi. "We hope through these tools to be able to foresee all of that, and try to solve the problem from what we see on the maps."

She adds: "We now have a different topography so we hope the maps will result in better planning, better cropping, better production."

For years, WFP has used cutting-edge GIS data to chart the course for programmes and the vehicles that deliver them in countries such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Haiti, Mozambique, and Syria.

Having supplied five mini-drones to Lesotho's Disaster Management Authority, in April WFP ran a six-day training in their use for 20 individuals.

As the daughter of a farmer, Moakhi is passionate about the tech. "I see my father at home being able to get better crops - he'll be able to plant correctly because he'll now know the kind of soil he has and the type of seeds that match that soil," she says.

"I see a less-eroded Lesotho. With our thematic maps, we'll be able to see all those places that are susceptible to soil erosion. We are now getting solutions to avoid erosion even before it comes."

Drone worship: Why sky's the limit for humanitarian WiFi

She adds: "I see my country saving many resources" through such preparedness. "The idea is to get people excited or interested in geospatial tools by showing them the dashboard".

As part of the initiative, WFP has trained 30 government officials from various ministries to equip users with skills to operate the platform. Last year, we provided technical assistance and training to more than 300 government officials on nutrition and the monitoring and evaluation of programmes.

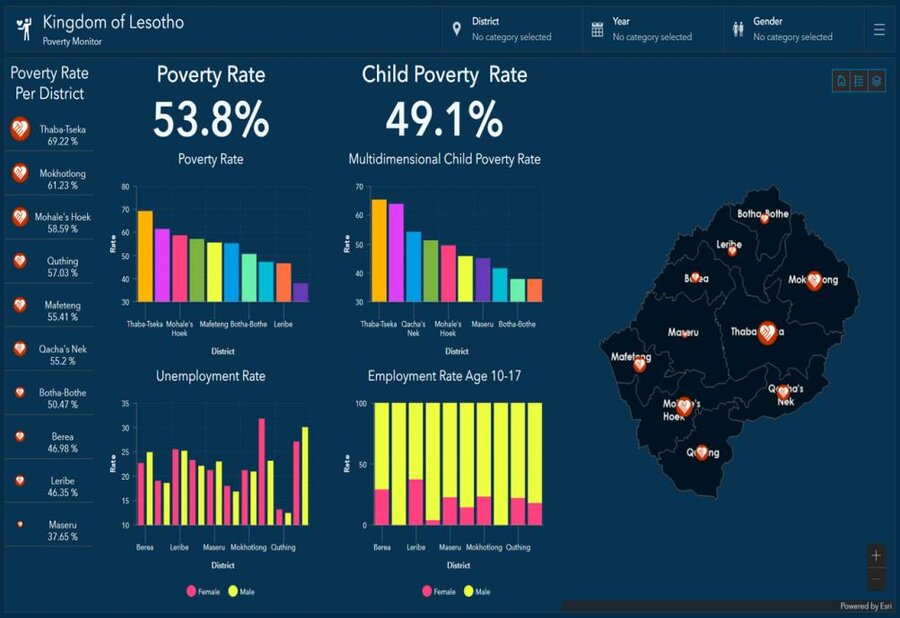

The scope of the tech is by no means limited to assisting farmers amid climate concerns. It can handle a host of Government concerns, such as poverty and crime too.

"We can overlay different socio-economic indicators on a single dashboard to make better-informed decisions," says Moakhi.

"We might once have assumed, say, that Leribe is the most impoverished part of the country when, actually, it is Mafateng - through the geospatial tools now you can analyze (layers of themed data). If there is a high rate of poverty, you can see why. You look at the population, you look at the level of education."

She adds: "Now you can say 'there is a high level of crime in Qachas Nek' and you realize that the level of education is lowest, you match all these layers together, and you see the poverty rate is higher.

"At the same time, the crime rate is high, the highest population in that area is of a specific age, and then… it begins to make sense.

"I realized through the tools that we might make decisions on a face value when there's actually a root cause - sometimes we are fighting crime when actually we're supposed to focus on the poverty rate. With this tool, we get layers of information."

The data maps can also play a role in empowering women and girls by identifying, for instance, where there are no roads and access to schools is limited.

This could result in more education centres being built, "more girls will go to school and more women will have access to economic empowerment".

Moakhi's vision is of a "generally a better country, a better economy" where "our families' livelihoods have improved." She adds: "Even the life expectancy in our country will improve, as the level of education improves."