Coral IVF is a world-leading technique to grow baby corals and use them to restore damaged coral reefs.

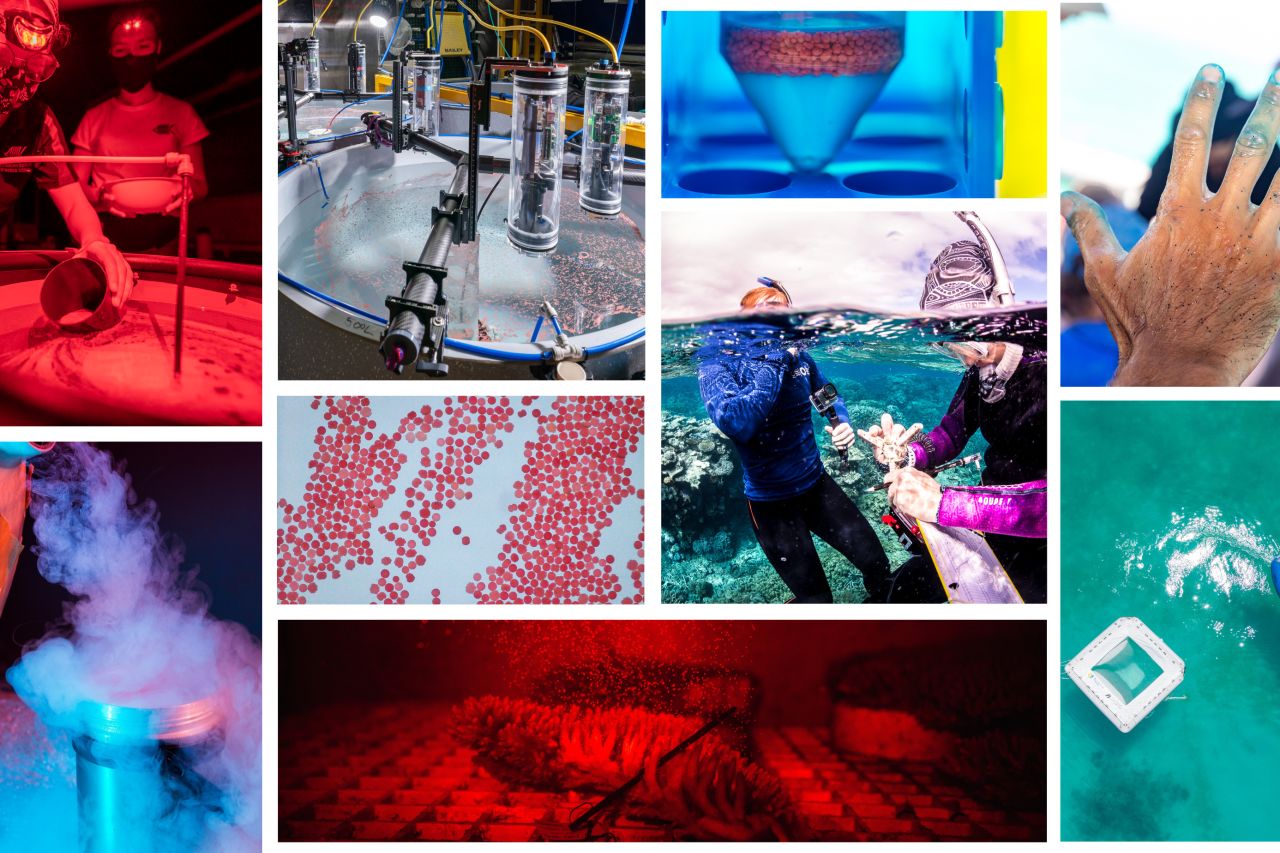

Our researchers capture coral eggs and sperm, called spawn, from healthy reefs and rear millions of baby corals in specially-designed floating pools on the Reef and in tanks. Researchers use these pools to encourage a higher rate of fertilisation and when they are mature enough, they are delivered to damaged reefs where they can attach and grow.

Floating larval pool nurseries Heron Island December 2020

#How do corals reproduce?

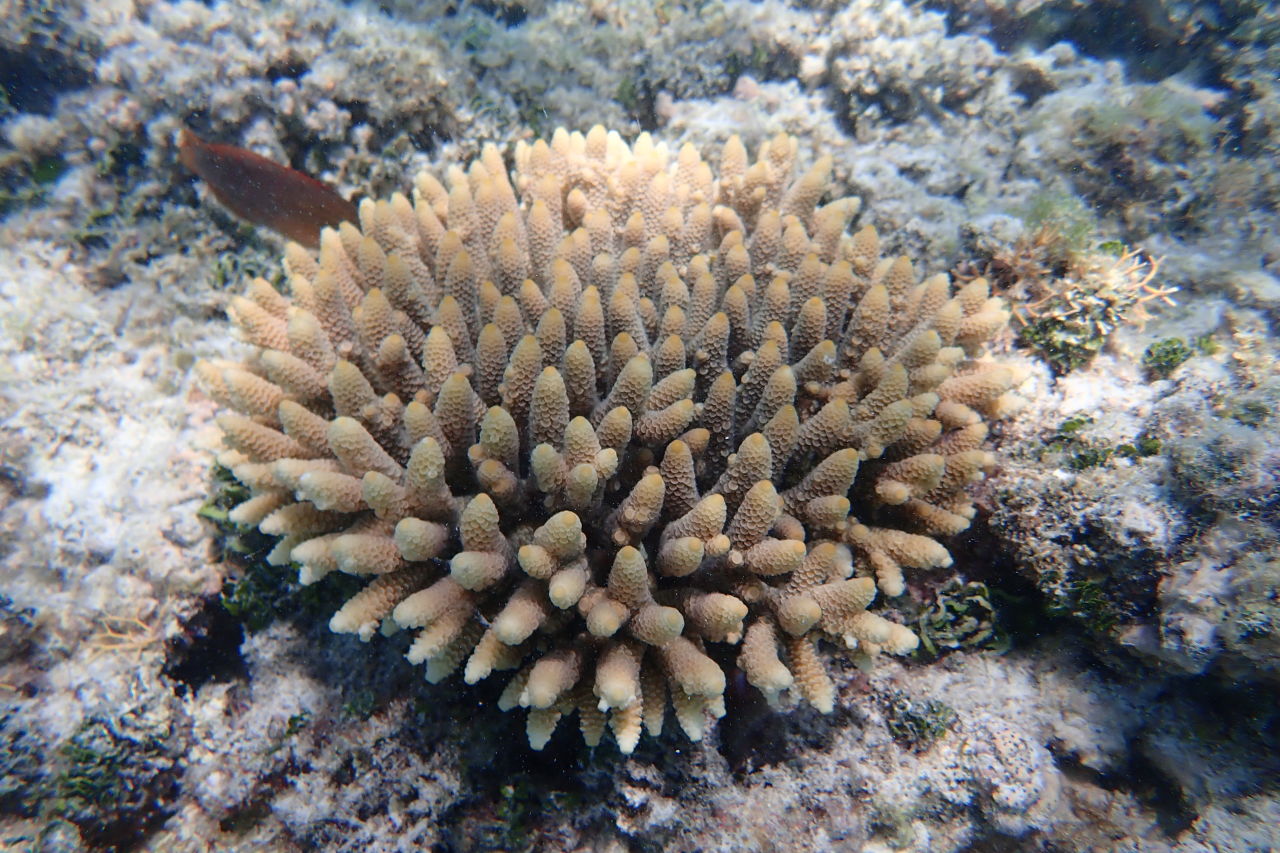

Many coral species on the Great Barrier Reef are known as broadcast spawners. As these species of corals reach adulthood and when conditions are just right, they produce reproductive bundles made up of eggs and sperm. For a few days once a year, different pockets of our Great Barrier Reef will synchronise the release of these reproductive bundles into the water to produce millions of baby corals. Spawning typically occurs a few days after the full moon in October or November, and can vary according to location, water temperature and the tides.

Once the bundles have been released, they rise to the ocean's surface where fertilisation begins and baby corals are formed. From here, a budding coral's challenges are just beginning. By spawning on mass, corals increase the likelihood of finding a matching bundle from the same species to fertilise. Other external factors like ocean currents and predation can impact their chances of finding their mate on the surface, which is why we're using methods like Coral IVF to increase their chances of love.

Spawning events are an exciting and busy time of year for Reef scientists, providing them with an opportunity to fast-track world-leading restoration efforts. They are also an extraordinarily narrow window for reef research and restoration efforts, reproducing for just a few days each year. Research teams work around the clock to collect spawn, and use it to grow new, resilient corals on the Reef or in special aquariums on land.

Corals spawn just once a year in a synchronised mass breeding event.

#Does Coral IVF work?

Our research team, led by Southern Cross University's Professor Peter Harrison and CSIRO's Christopher Doropoulos, began trialling Coral IVF on the Great Barrier Reef in 2016. Our first batch of Coral IVF babies were tiny - barely the size of a matchhead - and researchers hoped they would attach to the Reef and thrive. Within the first five years of their life, not only did these baby corals grow to maturity and survive a bleaching event, in 2021 they reproduced for the first time. This was the first time a breeding population had been established on the Great Barrier Reef using this ground-breaking process giving hope that this innovative technique could successfully restore damaged reefs.

Researchers deploy coral babies onto damaged reefs.

#Why is Coral IVF important?

Coral reefs around the world are facing a growing number of threats including climate change, which leads to increased water temperatures. Heat stress is one of the causes of coral bleaching and, while bleached corals can recover, severe bleaching events can kill large areas of coral reef. The Great Barrier Reef - the world's largest coral reef - has suffered three mass bleaching events in the past five years.

To help our Reef recover, we have more than 100-Reef-saving projects underway right now and the world's largest coral reefs program. We are developing, testing and deploying new techniques to protect and restore coral reefs at scale and help them resist and adapt to a changing climate. Coral IVF is just one of the innovative ways we're getting the most out of coral spawning.