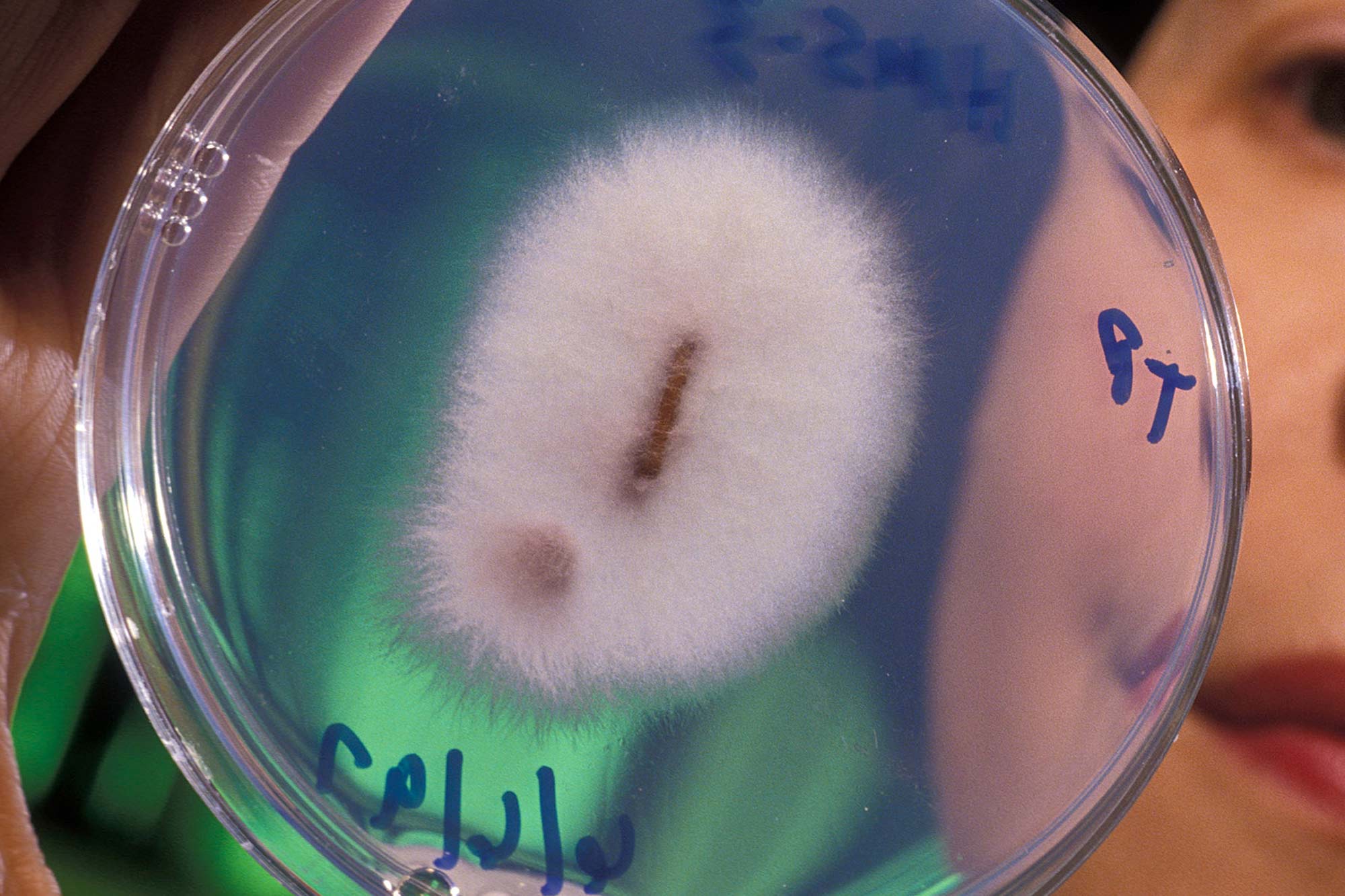

A researcher views a pathogenic strain of Fusarium oxysporum, a creeping parasite that causes Panama disease and threatens the bananas consumers enjoy. (Photo by Keith Weller, USDA Agricultural Research Service)

Some creatures hunt or scavenge to survive, while others freeload. Parasites make up the gross, but fascinating, latter category.

University of Virginia biologist Amanda Gibson studies and teaches about the range of survival strategies within that rogue's gallery of lifeforms that glom on.

"Students often understandably come in with misconceptions about parasites," Gibson said. "They're thinking like the 'Alien' movies or 'The Last of Us' on HBO, with things bursting out of people."

So what constitutes a parasite? Like a co-dependent paramour, they can't get by without you, and they ultimately harm your wellbeing.

Ticks, for instance, are parasites. A mosquito is not because it can bug off and be just fine without you. Tapeworms and other borrowers of bowels and flesh are parasites, as are decomposers such as fungi. But so are, debatably, bacteria and viruses.

The definition, Gibson said, often depends on who the host is and which scientist you're asking.

Gibson recently discussed five wild facts about parasites with UVA Today.

1. Parasitism is the most common survival strategy in the world.

In terms of body count, beetles constitute about a quarter of the 7.7 million known species on our planet, about half of which are themselves parasitic.

"There's this famous quote by evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane saying, 'It would appear that God has an inordinate fondness for stars and beetles,'" Gibson said.

They're also very often playing host to houseguests themselves.

Amanda Gibson is an assistant professor of biology with expertise in parasites and their survival strategies. (Photo by Erin Edgerton, University Communications)

"We know that for pretty much every beetle species, there are at least two or more tiny little parasitic wasps. These wasps lay their eggs inside the beetles and eat the beetles from the inside.'"

Numbers matter, because too many of a parasite, which can deplete an organism's vitality - even kill it - can have an outsized impact. Parasites may threaten humans either directly, or indirectly by way of what we eat.

But Gibson sees all the parasitic abundance, when in check, as a good thing.

"This means that contrary to popular conceptions of parasites as scourges, they in fact lie at the very heart of this earth's biodiversity," she said. "They are integral components of our food webs. They connect species to one another. They lay bare our interconnectedness."

2. Parasites will sometimes knock off individual hosts. (What's up with that?)

It may seem counterintuitive that a parasite might want to kill the organism keeping it alive, but that, too, can be a survival strategy.

"There has continued to be misconception in the field over this long-held idea that it doesn't benefit parasites to kill their hosts," Gibson said.

In fact, there are conditions under which highly virulent parasites make sense.

"You can imagine the advantage of killing your hosts, if killing them faster means replicating more," she said.

3. Thanks to parasitism, there likely will be another 'banana apocalypse.'

Yes, we will have no bananas, again.

Consider the case of the Gros Michel variety of banana, nicknamed "Big Mike." It became so popular that farmers produced it almost exclusively.

Unfortunately, a parasite that causes Panama disease swept over the monoculture, making it no longer commercially viable by 1965. That's why most consumers now eat a variety called Cavendish, which was resistant to the dominant fusarium wilt strain.

Yet that cultivar, too, is now threatened. A new strain of fusarium has evolved, jumping from Taiwan, where it originated, to other parts of Asia and Africa.

Parasites find creative way to live off their hosts, diminishing wellbeing. The parasite responsible for river blindness in Africa, onchocerca volvulus, emerges from the antenna of an adult black fly. (U.S. Department of Agriculture image)

"People are starting to talk about 'banana apocalypse' again," the professor said. "Farmers start planting the exact same genotype of banana, and then it just gets wiped out by a fungal pathogen. And so there's this idea that if I'm more closely related to my neighbor, I'm more likely to be able to pass my infection to them."

The good news is that there are varieties of bananas that are less cultivated and could fill in the gap in the fruit bowl if Cavendish disappears.

4. 'Hyperparasites' may or may not save us.

A "hyperparasite" sounds scary, right? Yet it's meant to be a helper.

Hyperparasites attach to host parasites, and humans sometimes set them up on blind dates to keep the hosts from becoming overabundant. The concept is a lot like the ancient proverb, "The enemy of my enemy is my friend."

Recent postdoctoral research in Gibson's lab looked at why the approach hasn't been so successful in practice. Specifically, the researchers studied root knot nematodes, which are responsible for killing up to 5% of the major vegetables you love: potatoes, carrots, tomatoes, lettuce, cucumbers and more.

The nematodes become sterile when infected with a specific bacterial parasite, yet they haven't consistently declined in numbers when the bacteria are applied to an agricultural field infested with nematodes.

"You should have lower numbers of nematodes, less nematode infestation, and your plants should be healthier and more productive," she said. "And there's some evidence that happens, but it's really variable. There are some fields where you add in the hyperparasite, and the nematodes seem unaffected."

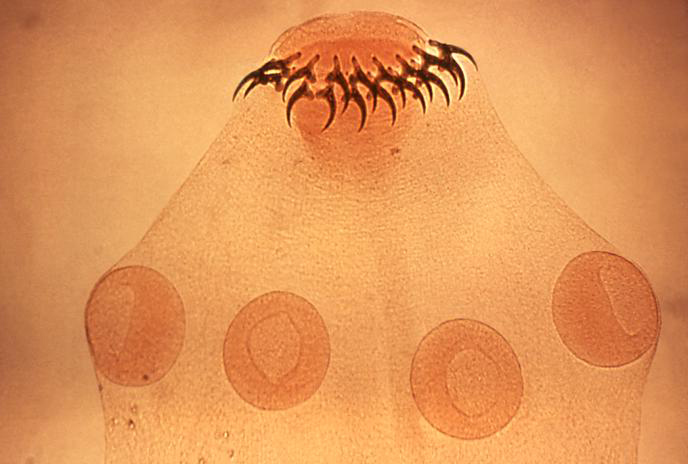

With their hooks and suckers, tapeworms seek attachment, as this microscope image demonstrates. (Centers for Disease Control image)

Gibson and researcher Fabiane Mundim, now a professor at Utah State University, determined in that adding diversity to the cocktail of bacterial parasites served may be the solution.

When the researchers did so, they doubled, on average, the number of nematodes that had the potential to be infected.

5. Forget "The Last of Us." Superbugs are the parasites to keep us up at night.

One of the more recent zombie dramas to give us the heebie-jeebies is "The Last of Us." While the fungus in question, Cordyceps, does control its hosts, in reality it only infects insects.

Gibson said a real-life parasitic horror story we should be worrying about is the spread of "superbugs" - parasitic bacteria that can't be killed easily.

The bacteria evolve resistance to antibiotics. Their adaptation is due to the constant pressure society has placed on them.

"Antibiotic resistance is probably the greatest public health threat that we face right now," she said. "And that is the direct result of how we've used antibiotic and how we've distributed them in both medical and agricultural settings.

"We created this problem. To some extent it was inevitable, but it didn't have to be as bad as it is."