Japan's Ryukyu Islands, which includes Okinawa, are the exclusive home to two rare mammals, the Amami rabbit and Ryukyu long-furred rat. These animals are hard to observe, but conservationists wish to find out specific details about their diets. So researchers, including those from the University of Tokyo, inspected the teeth from deceased specimens to find out what the animals were eating, and at different times. Their findings show the rabbits have consistent diets, whereas the rats' change with the seasons.

When you think about Japanese islands such as Okinawa, part of the Ryukyu chain in the southwest of the country, you may picture sun and surf, but hiding deep within the shady forests on these islands are plenty of small mammals who have been living there for millennia. Some, such as the Amami rabbit, are considered "living fossils," given their closest continental ancestors are long since extinct. They and another local resident, the Ryukyu long-furred rat, are both extremely rare. Given the increasingly complex and severe problem of climate change, and potentially other human impacts in the region, there are efforts to conserve these species.

"Climate change and human activity can adversely affect animals' environments. And this could be detrimental to their feeding patterns and food sources," said Associate Professor Mugino Kubo from the Department of Natural Environmental Studies. "Because of this, and to build a better picture of the lives of these rare animals, we aim to clarify the feeding habits of these species and gain insights into their ecology to inform conservation strategies. Our latest research was to explore the diets of the Amami rabbit and Ryukyu long-furred rat, specifically their seasonal variations."

Kubo and her team analyzed microscopic wear patterns, or microwear, on the surface of the teeth of both species, using three-dimensional texture analysis to determine what they eat throughout the year. The teeth came from wild specimens who had been killed on roads, and they compared those to teeth from laboratory-raised rodents who had known feeding histories. This comparison revealed what the wild populations were eating without the insurmountable effort of trying to monitor them, which would have been essentially impossible.

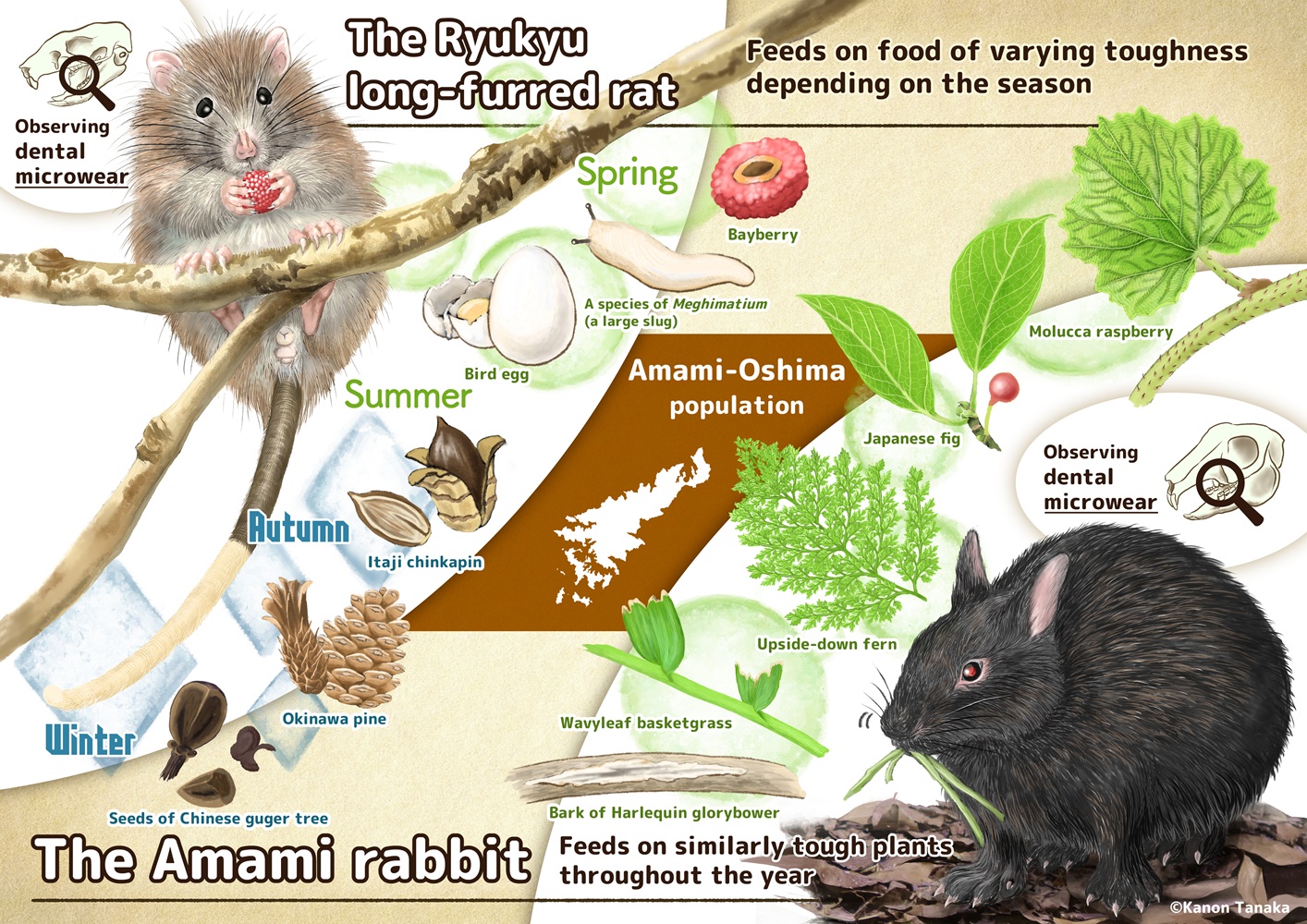

"Our results showed that Amami rabbits consume tough plants like ferns year-round due to consistent microwear; whereas the Ryukyu long-furred rats change their diet seasonally, feeding on soft foods like fruit, slugs and eggs in summer, and hard foods like seeds and acorns in winter, according to varying microwear," said Kubo. "This research demonstrates that dental microwear texture analysis can reveal feeding habits of rare species difficult to observe directly in the wild. Moreover, our findings suggest ecosystem management should consider seasonal dietary differences more carefully."

The team plans to expand on this research by comparing populations of these same species across different islands within the Ryukyu chain. They also intend to use DNA analysis and other methods to gain an even deeper understanding of the dietary habits of these species.

"While this study did not directly address the impact of human activity, previous research has shown that the unique ecosystems of the Ryukyu Islands are threatened by human activity, leading to population decline," said Kubo. "Future comparisons with older museum specimens may reveal changes in diet or ecology caused by recent human activity."