One of the biggest challenges they faced was finding an effective way to share their data and results. Another challenge was making sure their research informed the response of public health officials and healthcare workers to the pandemic.

For the first time on such a scale, science, public health and healthcare came together to tackle a virus that had managed to make its way into almost every country. EMBL's European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) is using its data sharing expertise to help address some of these challenges.

How does data help?

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes the illness named COVID-19, had never been seen in human populations until this year. It's part of a known family of viruses, called coronaviruses, and is closely related to the viruses that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), but we know little about its specific features.

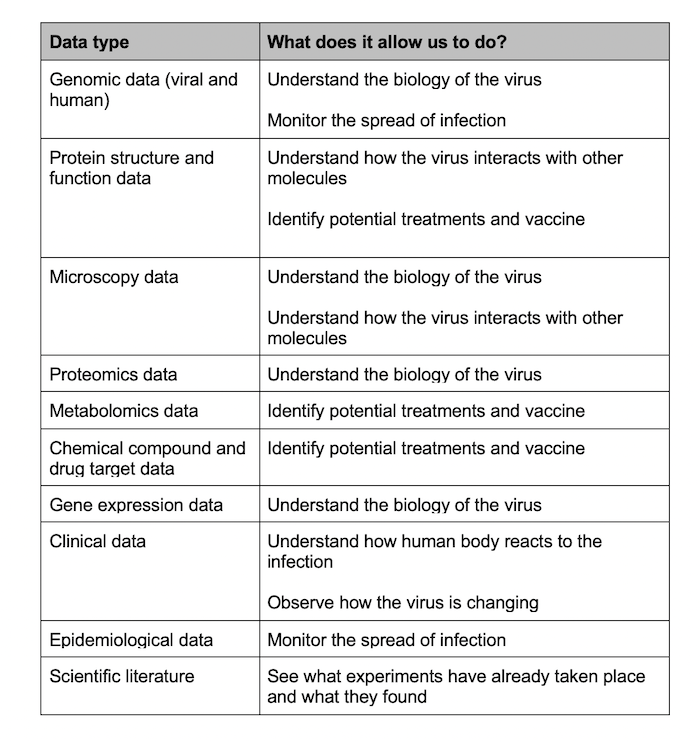

There are several things we need to understand about the biology of a virus to help us figure out how it infects people, how it spreads, and most importantly, how it can be treated using drugs or prevented through vaccines.

"We need many different types of data to answer the key questions about the new coronavirus," explains Edith Heard, EMBL's Director General. "From genome sequencing to protein structures and from chemical compounds to microscopy data, there are many pieces of the puzzle that will eventually come together to give a clear picture of how this virus operates and how it can be stopped. The issue is that the data are coming from hundreds - maybe even thousands - of labs around the world, so bringing them together is very challenging."

Sharing data - it's what we do

EMBL-EBI is a leading centre for biomolecular data. With over 40 data resources and many more data analysis tools, EMBL-EBI stores, shares and analyses data produced by life scientists all over the world.

When the new coronavirus outbreak began, EMBL-EBI started receiving relevant scientific data from different groups all over the world.

"By February our teams were highlighting information submitted about the new coronavirus and sending it to a dedicated page on our Pathogen Portal," explains Guy Cochrane, Team Leader for Data Coordination and Archiving at EMBL-EBI. "Our colleagues made huge efforts to check and share the increasing amount of data that was coming in from all over the world. This way, we gathered much of the relevant information in one place."

When EMBL-EBI closed its doors on 18 March, to protect staff and visitors from the pandemic, the work continued remotely. From their living rooms or kitchens, often with slow internet connections or combined with childcare, EMBL-EBI teams continued enabling scientists to share their data. And a much bigger plan was in the works.

Building a data portal

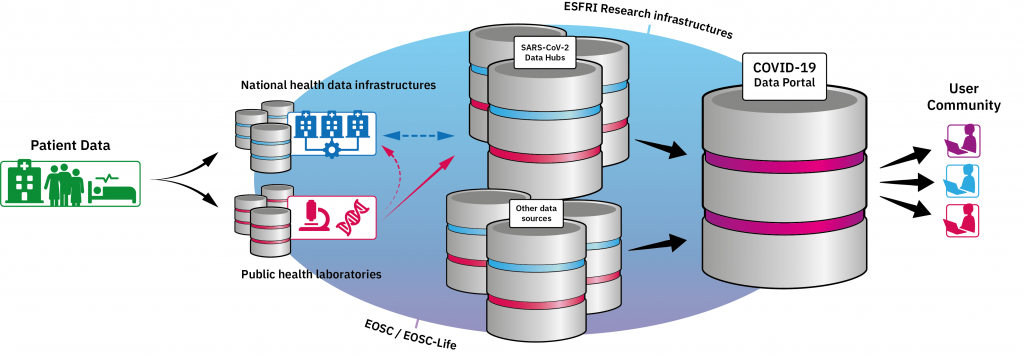

"Bringing together all the research data we hold at EMBL-EBI is a good start, but it's not enough," says Amonida Zadissa, Senior Scientific Services Officer at EMBL-EBI. "We have to coordinate with other biomolecular centres that hold relevant data and, more importantly, we have to make the data useful downstream, to public health professionals and healthcare providers."

EMBL-EBI has now set up the COVID-19 Data Portal, a single place where researchers can upload, share and access data related to the new coronavirus. So far, the portal includes data from EMBL-EBI databases and information from collaborators in four countries.

The race for a genome

When the new coronavirus was first identified in China, it took scientists only a few days to sequence its genome and make the sequence publicly available. The genome is the virus's entire genetic code and it contains clues about how the virus evolves, how it spreads and how it can be treated.

The fact that the genome was published online within a few days is an enormous scientific achievement, and shows the advances in sequencing technology that have occurred since the SARS outbreak in 2003. At that time, it took almost three months to sequence the virus's genome. The speedy publication of the new coronavirus genome gave the world a huge advantage in the race against the pathogen, bringing forward vaccine testing.

What can genomic data tell us?

While sequencing the whole genome of the new virus is crucial, it is not enough. It's also essential to sequence the genetic material of the virus from samples collected all over the world. This will help scientists to monitor the outbreak and how the virus is evolving.

Bringing together sequencing data from different sources is more difficult than it sounds, because of the different sequencing technologies used, the different languages in which the data is described, and so on. Luckily, harmonising or "cleaning up" data in this way is one of EMBL-EBI's areas of expertise.

Alongside the COVID-19 Portal, EMBL-EBI is facilitating the set-up of national SARS-CoV-2 Data Hubs across Europe where scientists can internationally share any genomic data related to the virus. These hubs will be used by public health agencies and research centres doing genome sequencing of the new virus at national or regional levels.

EMBL-EBI is already collaborating with Erasmus Medical Centre in the Netherlands, the Technical University of Denmark and Eötvös Loránd University in Hungary, with more collaborations to be announced in the following months.

Apart from the raw data, metadata will also be available when possible, for example how and where the raw data was collected, what technology was used, and the health status of the patient. This helps scientists understand who is more likely to get the disease and develop severe illness.

In addition to genomic data, the COVID-19 portal contains a number of other data types that give different insights into the virus.

We're in this together

"The global response to the new coronavirus is crossing boundaries between scientific disciplines, including genomics, epidemiology, medicine, drug discovery and vaccine design," says Zamin Iqbal, Research Group Leader at EMBL-EBI. "It will also cross national borders and healthcare systems, and will require unprecedented levels of international cooperation."

"While we're in the midst of the pandemic it's hard to imagine that anything good will come out of it. But perhaps one positive thing is that scientists and public health laboratories and agencies are working together more than ever. They're also setting up processes and mechanisms for collaboration that can be used again, should a new virus arise. All of these efforts are improving how we do things now and they must inform future decisions regarding pandemics."

In the midst of the epidemic, EMBL-EBI is continuing its mission to make the world's biological data openly available and looking for collaborators to help.