This article is an excerpt from the research magazine "Tackling Global Issues vol.3 Fighting the menace of zoonosis." Click here to see the table of contents.

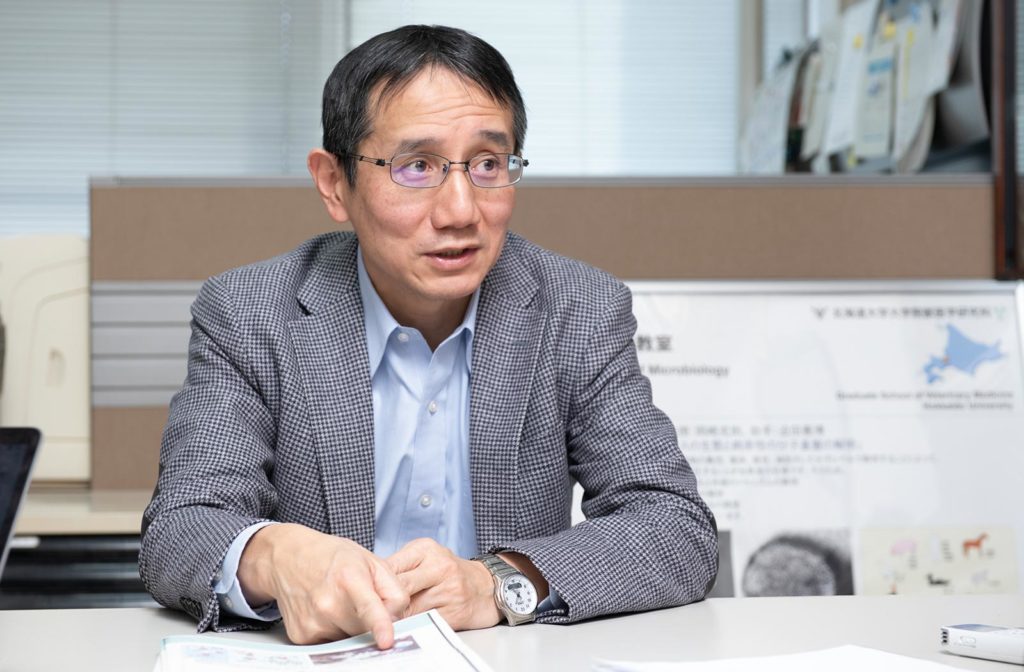

Yoshihiro Sakoda, DVM, Ph.D.

Professor at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Research Center for Zoonosis Control (CZC)

Research areas: Avian influenza, microbiology, disease control

Responsible Official of the OIE Reference Laboratory at Hokkaido University

From April to June in 2013, 43 cases of a low pathogenic avian influenza were reported among poultry and wild pigeons in nine provinces, one city and two autonomous regions of China. This influenza, caused by the H7N9 virus strain, took many specialists by surprise because few of them had expected such a virus subtype would emerge to infect birds.

As the virus infection was repeated among poultry, the virus became highly pathogenic, killing birds and then humans. According to the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 1,568 cases of human infection have been reported, including 616 fatal cases.

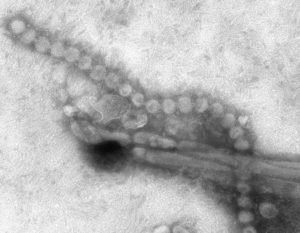

Electron microscopic image of H7N9 influenza virus. Photo courtesy of CDC/Cynthia S. Goldsmith and Thomas Rowe

There was, however, one institution that had stockpiled the H7N9 virus just in case such a virus began to infect birds: the Research Center for Zoonosis Control (CZC) of Hokkaido University. "Our strategy of having all 144 avian influenza virus subtypes ready and stored in a library was worthwhile," said Yoshihiro Sakoda, who is a key architect of the avian influenza virus library at CZC, which stores all 144 combinations of hemagglutinin (HA; a glycoprotein) and neuraminidase (NA; an enzyme) subtypes. Eighty-one combinations of HA and NA subtypes have been isolated from fecal samples of waterfowls in surveillance studies. The 63 other combinations were generated by the genetic reassortment procedure in embryonated chicken eggs.

"Because of our preparation, we were able to write a report about human vaccination against the H7N9 influenza right after its outbreak," Sakoda said. "It is crucial to have preemptive measures in place."

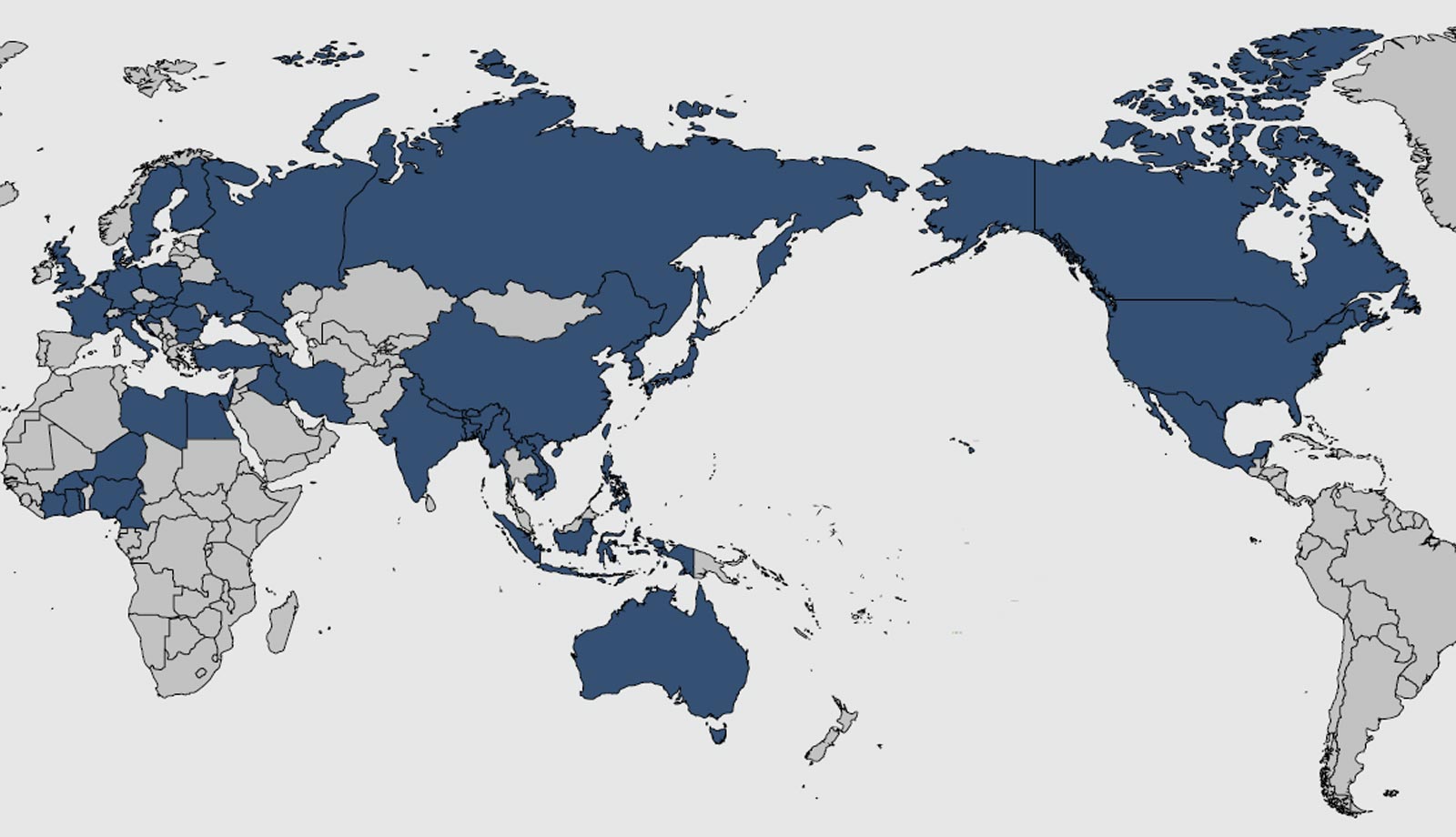

Spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza

The most prominent emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus dates back to 1996, when the H5N1 virus strain was first detected in geese in China. It is highly contagious among birds and can be deadly for poultry. Human infection was first reported in 1997 during a poultry outbreak in Hong Kong and has since been detected in poultry and wild birds in more than 60 countries in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East. Four countries - China, Egypt, Vietnam and Indonesia - are considered to be endemic for H5N1 in poultry. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 861 cases of humans infected by the H5N1 strain, including 455 fatal ones, were reported as of January 2, 2020.

The countries that have experienced a highly pathogenic avian influenza incident since 2014. (Adobe Stock © pyty).

According to Sakoda, the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza across the world can be blamed on the explosive increase in the global population, which has driven up demand for more sources of protein. "Humans are in fact accountable for the spread of avian flu viruses because of the need for more poultry farms," Sakoda said. When a large number of birds are kept in a small space, a virus can spread easily and quickly, gaining higher pathogenicity in the process. "The lack of hygiene measures at such farms has helped preserve influenza viruses of various subtypes in the environment and spread highly pathogenic influenza around the world via migratory birds," Sakoda said.

Although no human infection in Japan has been reported, people have been infected in China and Southeast Asian nations, where live poultry markets are thriving. Sakoda said people working at live bird markets are exposed to a huge amount of viruses and some accidentally contract the viral infection.

So far, there has been no reported human-to-human transmission of avian influenza. However, the possibility of human-to-human transmission cannot be completely ruled out. Sakoda said eradicating avian influenza is essential under the One Health concept, which recognizes that the health of animals and humans are interrelated.

Some obstacles in containing avian influenza are difficulties in improving hygiene at live poultry markets in Asia. (Chicken market in Xining, Qinghai province, China, below.) © M M (Padmanaba01).

Obstacles in containing avian influenza

"The best way today to contain avian influenza is to cull all chickens at contaminated poultry farms, disinfect the farms and take all possible measures to stop the viruses spreading from them," Sakoda said. They had researched how to control avian influenza based on scientific evidence long before the 2004 outbreak in Japan, and that is why it was handled very effectively, according to Sakoda. Since then, Japan has detected influenza viruses in wild birds and limited contamination of poultry farms, but its control of the avian disease is considered one of the best in the world. "Some people oppose culling, but it is really necessary for helping farmers return to their business as soon as possible," Sakoda explained.

However, culling is not an option for such countries as China, Vietnam, Indonesia and Egypt, where avian influenza is endemic. Instead, they vaccinate poultry.

This approach, Sakoda said, is problematic in that it will spread "hidden infections" because vaccinated chickens develop less serious symptoms than unvaccinated ones, but can still spread the viruses.

Improving hygiene at live poultry markets in Asia is a daunting task. Many developing nations lack cold-chain logistic systems to transport fresh meat safely from farms to consumers. "Crafting such a system is important for preventing people from getting exposed to avian viruses at live poultry markets and for preventing the viruses from proliferating," Sakoda said.

Furthermore, poultry farmers in those countries are often unwilling to cull their birds because there is no subsidy program to cover the resulting financial damage. Some developed nations give handsome subsidies to affected farmers.

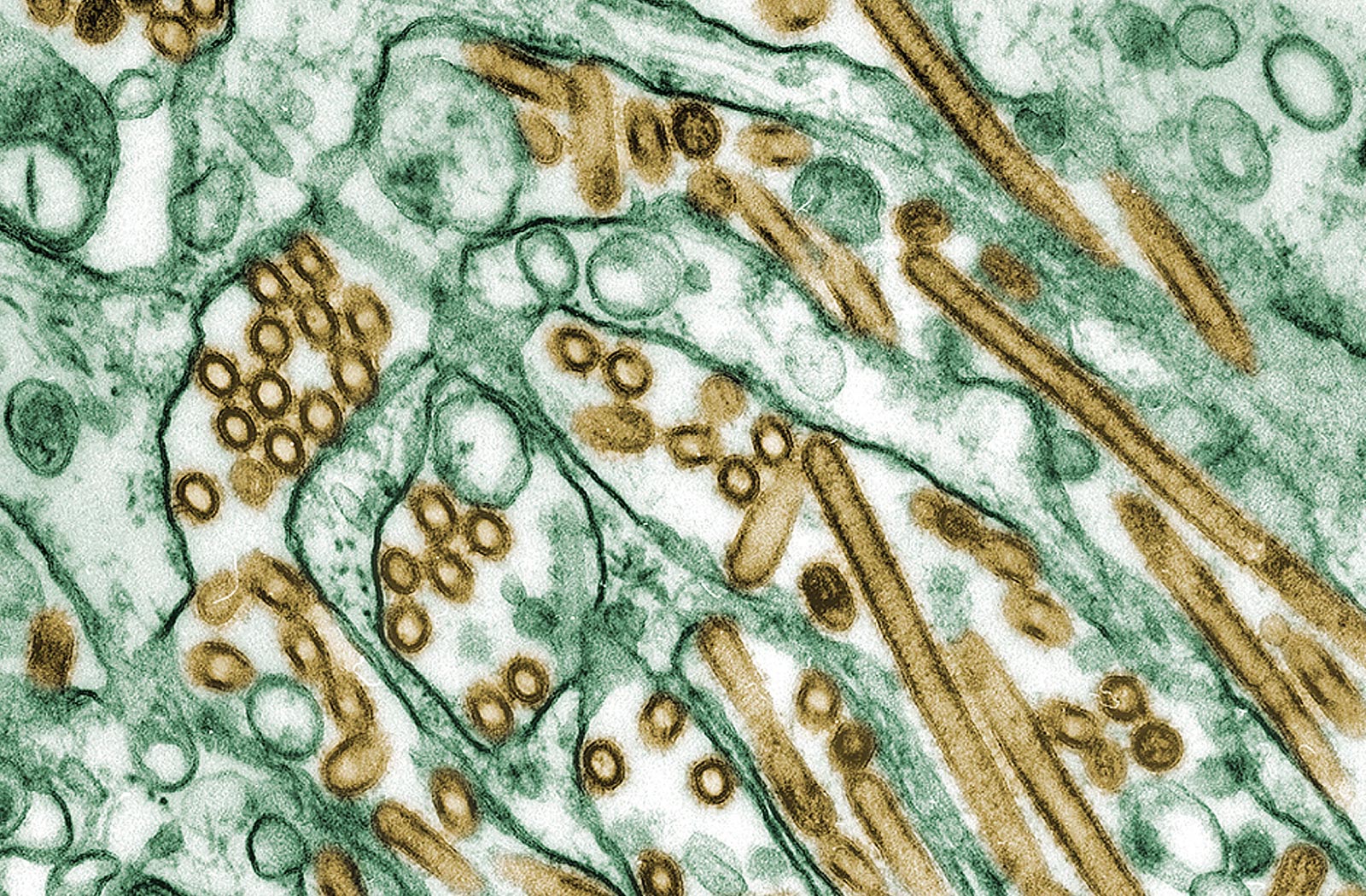

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (brown) grown in cultured cells (green). Avian influenza A viruses do not usually infect humans, but several instances of human infections and outbreaks have been reported since 1997. Photo courtesy of CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith; Jacqueline Katz; Sherif R. Zaki

Global surveillance is essential

Hokkaido University is one of the nine World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) Reference Laboratories tasked with supporting the diagnosis of avian influenza, developing necessary diagnostic methods, and providing scientific and technical advice to other Asian countries.

Hokkaido University is one of the nine World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) Reference Laboratories tasked with supporting the diagnosis of avian influenza, developing necessary diagnostic methods, and providing scientific and technical advice to other Asian countries.

Hokkaido University has already developed an innovative, easy-to-use diagnosis kit capable of rapidly identifying virus subtypes in the field or on farms. "We are doing it for the benefit of Asia," Sakoda said. "If the spread of the viruses is contained elsewhere in Asia, there will be a smaller chance that migratory birds will infect poultry in other countries. We have to take a leading role in helping eradicate or contain avian influenza viruses in China and Southeast Asian nations."

Sakoda collecting feces of ducks and swans that flew from Siberia during a survey in Wakkanai, Hokkaido, the northernmost part of Japan.

Global surveillance of avian influenza is also essential. Wild waterfowls such as ducks are natural hosts to influenza viruses, which are not harmful to them. But they can spread the viruses around the world as they migrate, which could later become highly pathogenic. "By monitoring viruses those migratory birds bring, we can warn poultry farmers to take protective measures when the risk grows," says Sakoda.

Hokkaido University conducts surveillance in Japan, Mongolia and Vietnam. "If the viruses kill migratory birds or poultry, it will be unfortunate," Sakoda said. "But we can turn this misfortune into a prime opportunity to control the viruses if we thoroughly examine the viruses and make the results available to countries that have not experienced an outbreak."

Working toward the eradication of avian influenza

Sakoda is a graduate of the School of Veterinary Medicine. He returned to Hokkaido University in 2001 as a research assistant under Dr. Hiroshi Kida, now CZC head, after a seven-year-stint at the National Institute of Animal Health, where he conducted extensive research on swine fever.

When Sakoda returned to the university, Kida told him to continue researching swine fever while also studying avian influenza. Kida said, "Each researcher should have their own research topics." Sakoda's years of research on swine fever, which made him one of the world's foremost experts on the subject, has helped Japan deal with the swine fever outbreak that began in 2018.

Nonetheless, Sakoda remains committed to working toward the eradication of avian influenza. "If we can properly control avian influenza viruses, I think their eradication is possible," he said. "I want to see that before I retire from the university 15 years from now."

Click here to see the table of contents.