In a new study, researchers from UC San Francisco and Vanderbilt University Medical Center have identified specific immune cells that drive deadly heart inflammation in a small fraction of patients treated with powerful cancer immunotherapy drugs.

The researchers also identified the cells in heart muscle that is targeted by the destructive immune cells, and their new findings already have led them to begin investigating better ways to prevent or treat this potentially lethal heart inflammation, called myocarditis.

The form of myocarditis they studied is an infrequent but deadly side effect of cancer immunotherapy drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

ICIs target proteins in the body that serve as gatekeepers on immune system responses, holding unwanted inflammation in check. But blocking these checkpoint proteins with ICIs releases the brakes on immune responses - helping the immune system to attack established tumors effectively. ICI treatment has proved lifesaving for many cancer patients.

According to Javid Moslehi, MD, William Grossman Distinguished Professor and section chief of Cardio-Oncology and Immunology for the UCSF Heart and Vascular Center, fewer than one percent of patients who receive checkpoint inhibitor treatment, first approved in 2011, develop myocarditis. But nearly half who do experience this inflammatory immune reaction die as a result.

Moslehi co-led the new study, published November 16, 2022 in Nature, with cancer biologist Justin Balko, PharmD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine and pathology at Vanderbilt. They first described the clinical syndrome of ICI-myocarditis in 2016.

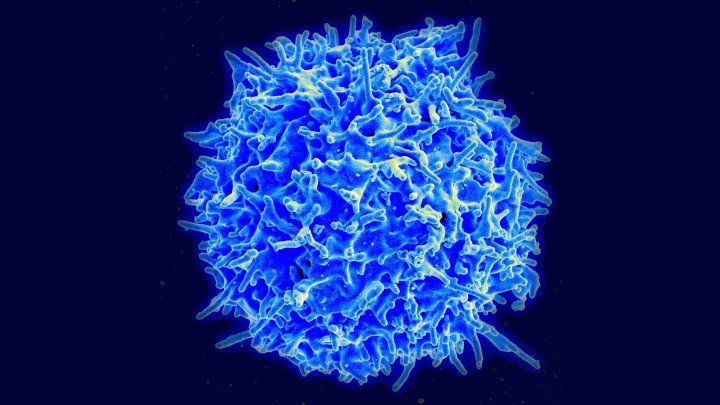

To mimic human ICI-caused myocarditis in the new study, the researchers used a strain of mice in which the same proteins targeted by ICIs in humans were instead genetically knocked-out. They found that immune system cells called CD8 T lymphocytes predominate in inflamed heart tissue of mice afflicted with myocarditis.

These same activated T cells are necessary to trigger myocarditis in ICI-treated cancer patients the researchers concluded, and therefore immunosuppressive therapies that affect CD8 T cells might play a beneficial role, they say.

"We earlier observed many T cells in patients who had died, but in the mice we performed several key experiments to show that the T lymphocytes really are drivers of the disease process, and not merely innocent bystanders," Moslehi said. "There are therapeutic implications to this study."

The research team already has reported a case study in which they used Abatacept, a rheumatoid arthritis drug that suppresses the activation of CD8 T cells, to successfully treat myocarditis in a cancer patient.

In the Nature study the scientists also discovered that the CD8 T cells that were selectively activated and that proliferated in clone-like fashion in myocarditis were those cells which targeted a key protein involved in muscle contraction in the heart, called alpha-myosin heavy chain (alpha-MHC).

The researchers then examined biopsy and autopsy tissue from three ICI-treated cancer patients afflicted with myocarditis and determined that in humans, too, the most prevalent CD8 T cells that had expanded clonally were those that targeted alpha-MHC.

"What was interesting is that the T cell receptors, which are basically identity barcodes of the T lymphocytes, that were specific for alpha-MHC were identical in the affected hearts, meaning that they were likely going after the same target," said Balko.

The researchers are testing T-cell directed therapies, and doing research to see if CD8 T-cell activation in ICI-induced myocarditis also stimulates the immune system to make antibody-producing B cells that target alpha-MHC. The researchers are thinking about ways to get the immune system to stop attacking alpha-MHC, through a process of tolerization, similar to the way allergy shots work.