It could happen if the tunnel is long enough, but the chances are basically zero

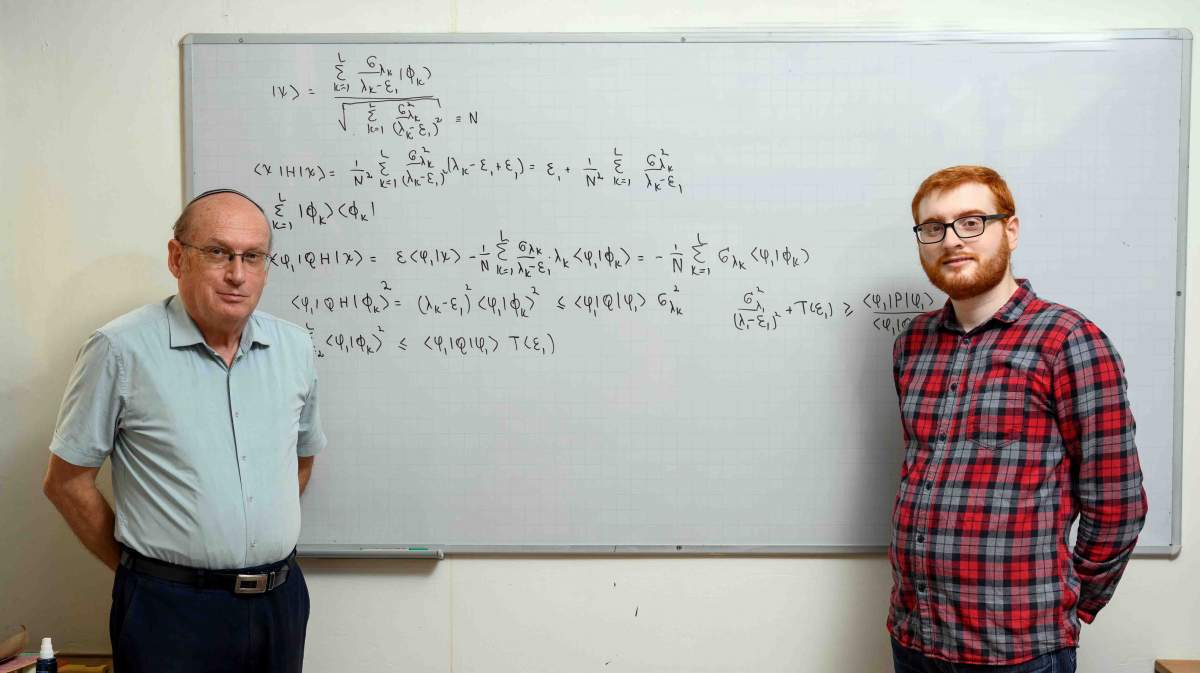

How much time does it take to send a package from New York to Tel Aviv, and how does that compare with sending an email from one side of the Weizmann Institute of Science campus to the other? Now shrink the package down to the size of one of the electrons making up the email and put up an impenetrable barrier over the ocean. The "package" electron could make the crossing faster, even breaking the light "speed limit." Prof. Eli Pollak, together with postdoctoral fellow Dr. Tom Rivlin, both of the Weizmann Institute's Chemical and Biological Physics Department, and Prof. Randall Dumont of McMaster University in Canada, recently provided theoretical support for this idea.

Impenetrable barriers are integral to one of the more fascinating quantum phenomena: tunneling. For around ninety years, researchers have been studying the way that quantum particles are able to pass through such barriers. In the 1960s, Thomas Hartman added a strange twist to tunneling: He showed that tunneling takes a fixed amount of time, no matter what length "tunnel" the particle transverses. That means that a particle could speed up while tunneling, and to make its goal in that fixed amount of time, it might even surpass the speed of light - if the tunnel is long enough or the barrier thick enough. Of course, this idea does not fit with the precepts of relativity - neither special nor general relativity - which are quite strict in insisting that particles cannot exceed the speed of light. Still, most researchers were not overly concerned with the results of this study, since it was already known that quantum mechanics and the physics of relativity do not jibe in many ways.

Therefore, so the thinking has been, this is another apparent anomaly that will work itself out once we figure out how to reconcile relativity with quantum mechanics. Pollak and his colleagues recently developed a new calculation of Hartman's idea, basing it on equations for quantum behavior first developed by Paul Dirac, which enable one to perform quantum mechanical calculations that are consistent with special relativity.

Their results support the scenario in which a particle is traveling in a tunnel and the timing of the process is a constant, independent of the length of the tunnel (or the thickness of the barrier). Theoretically, if the barrier is very long, the particle may reach the end of the tunnel faster than if it had just flown to the same destination in open space with no barrier in the way. And if the particle normally travels near the speed of light, then a tunneling particle would be able to get there faster than the speed of light.

Back to those emails: Could this finding enable us to send our information faster than the speed of light? The answer, to the likely disappointment of some and relief of others, is no. Prof. Pollak: "The chances of a particular particle tunneling are quite small, and those chances decrease exponentially as the length of the tunnel or thickness of the barrier increases. So the odds of the particle carrying our information making that faster-than-light trip through the tunnel are basically zero. For now, we'll have to content ourselves with the speeds of the existing options for sending packages and information, even if they do move slower than the speed of light."