Greening the way we eat needn't mean going vegetarian. A healthy, more realistic solution is to adopt a flexitarian diet where seafoods add umami to "boring" vegetables. University of Copenhagen gastrophysicist Ole G. Mouritsen puts mathematical equations to work in calculating the umami potential of everything from seaweed and shrimp paste to mussels and mackerel.

Most of us have a tough time eating enough veggies. According to the World Economic Forum only one in 10 people in the EU are getting the five portions of fruit and vegetables a day that are recommended both for the sake of health and climate. Which is natural, according to Ole G. Mouritsen, professor emeritus of gastrophysics and culinary food innovation at the University of Copenhagen's Department of Food Science. According to Mouritsen, vegetables just don't taste all that good on their own:

"Most people don't change the way they eat just for the sake of the climate. To really get things going, I think that every meal needs to be prepared to satisfy our sense of taste. And, when many people have a hard time eating enough vegetables, it's because vegetables lack the sweetness and umami that we've been evolutionarily encoded to crave."

WHERE UMAMI COMES FROM

There are only a few instances in which animal sources can be avoided when out to produce umami without fermentation. One exception is mushrooms, the other is a range of algae - including some of the larger seaweed species. Furthermore, umami is found in a few ripe fruits, such as tomato.

Mouritsen provides a scientific explanation for the abundance of umami in the animal kingdom:

"Just as there is a scientific reason for why plants lack umami, there is also a reason why the animal kingdom is the best supplier of umami and umami synergy. The substances that create umami are something that muscles use and are therefore absent in plants. When nucleic acids - the substances responsible for energy in muscles - are broken down, they produce substances called nucleotides. When these are combined with substances from proteins, such as glutamate, umami synergy is created."

So, if we are to realize a green transition of our eating habits with diets that are far more plant-based, it might be a good idea to liven up vegetable dishes with more umami - the basic, brothy taste typically associated with meat. Here, Professor Mouritsen believes that the sea is a low-hanging fruit. Not only does the sea abound with protein, vitamins, minerals and healthy fats, but also in much-coveted umami.

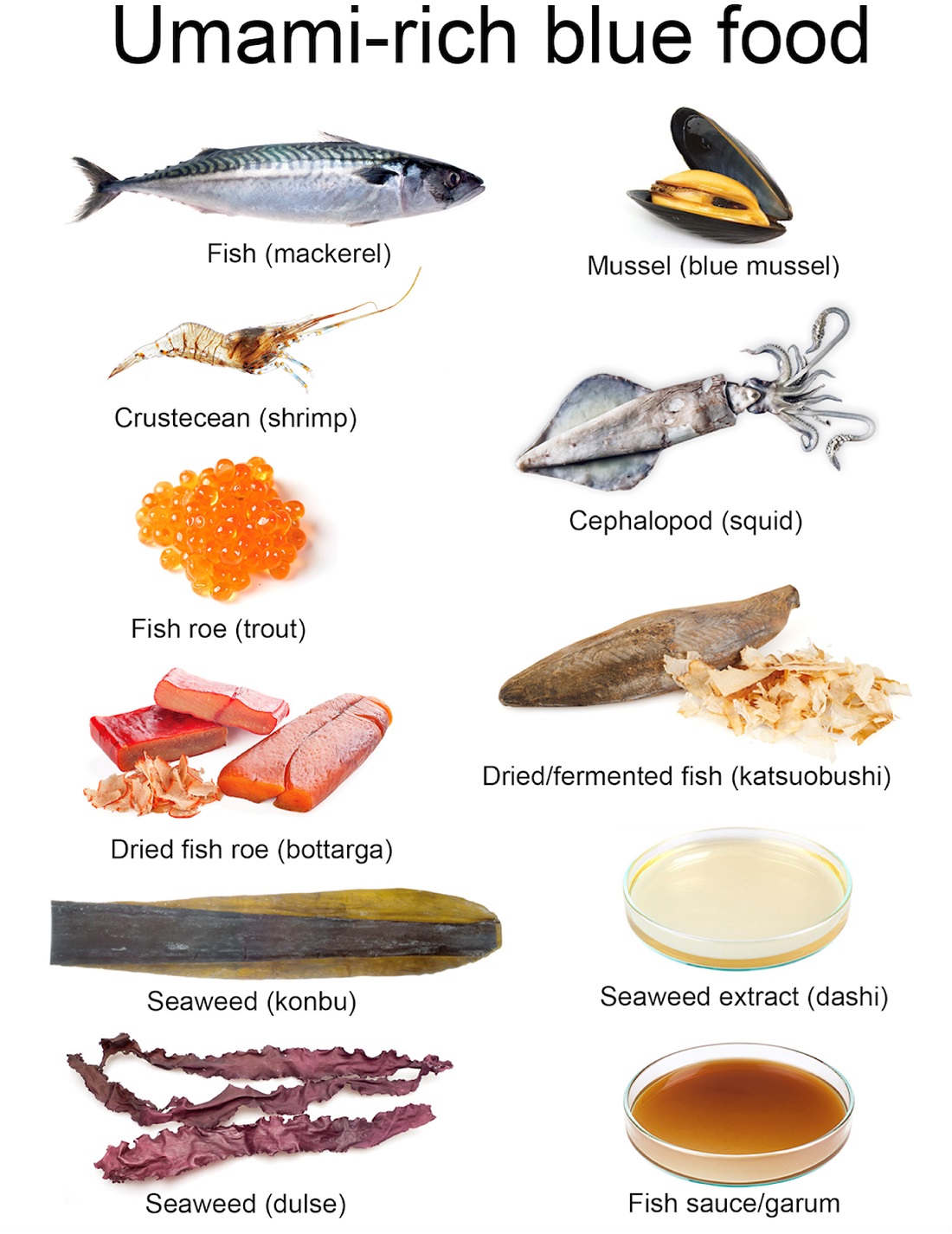

"We overlook the most readily available, and in many cases, most sustainable food sources with umami taste in them - namely fish, seaweed, shellfish, molluscs and other seafoods. If the right species are chosen, we can use them as climate- and environmentally-friendly protein sources that are also effective umami flavourants for vegetables," says Ole G. Mouritsen.

Using math to quantify umami

In a new scientific research article, Mouritsen uses a mathematical equation to help calculate the power of umami in a wide range of seafoods and demonstrate their great taste potential.

"Umami can be plugged into a formula because we know exactly how the taste receptors in our taste buds pick up on umami at the molecular level. There is a synergistic effect when two substances, glutamate and nucleotides, are present in a food at the same time. Glutamate imparts the basic umami taste, which is then enhanced many times over by nucleotides. This synergy is reflected in the equation," says Mouritsen, whose background is in theoretical physics.

The equation looks like this: EUC = u + u × ΣN γ(N)v(N)

EUC stands for Equivalent Umami Concentration, which is the umami concentration in a food expressed in mg/100 g.

The list of seafoods with large concentrations of umami is long. It includes everything from fish like cod and mackerel, to shellfish and molluscs like shrimp and octopus, to the roe of alaska pollock and blue mussel, to various types of seaweed and on to processed seafood products like anchovy paste and fish sauce.

"There are many possibilities. And while some people will probably debate the formula's accuracy, it doesn't matter. Whether the umami concentration in shrimp, for example, is 9,000 or 13,000 mg/100 g is not critical, as each is much greater than 30 mg/100 g, which is the taste threshold for umami," Mouritsen points out.

Working wonders with the right sauces and dressings

Only a few drops or grams of blue foods are usually needed to elevate vegetable dishes to something that satisfies our inherited umami craving.

SEAFOOD IS BRAIN FOOD

Seafood offers yet another distinct advantage over entirely plant-based diets according to Professor Mouritsen:

"Many of the essential nutrients in seafood are not found in plants - including vitamin B12. And one of the most important are polyunsaturated fats, which are created by algae, way down at the bottom of the food chain. Fish, shellfish and molluscs absorb these fats by eating animals that eat other animals that have eaten algae. These fats are very important for our nervous system and brain."

"Fish sauce and shrimp paste are obvious choices that some may already have in their kitchens or be familiar with from Asian cuisine. You can easily make sauces, dressings and marinades with them that elevate the taste above the threshold which brings out the umami in a vegetable dish," says Ole G. Mouritsen.

While it is easy for people preparing food in their kitchens at home to take part, it is first and foremost the professionals that Ole G. Mouritsen seeks to enlist.

"I've worked with chefs who have no problem preparing dishes where there is no compromise in taste, even when only a few grams of animal protein are present. It's a question of knowledge. And as scientists, we have a duty to share our knowledge," says the professor, who adds:

"Globally, many millions of meals are prepared daily outside the home - in canteens, hospitals, by meal delivery and recipe box services, in restaurants and in other contexts. It's the chefs, nutrition assistants and other culinary artisans who make the meals that, with the right knowledge, can move things forward."

We should be flexitarian

Professor Mouritsen believes that flexitarian diets are a more viable option than today's focus on replicating meat products using plants:

Many people know fish sauce from Asian cuisines, where it is used to endow dishes with umami. But Europe too once had a tradition of using fish sauce to impart extra flavor. Garum was used in nearly all ancient Greek and Roman dishes. It was often mixed with other ingredients, including honey. This garum was known as meligarum and consists of:

- 1 part fish sauce

- 2 parts honey

- 2 parts citrus juice

One quick use of meligarum is as a dressing or marinade for pointed cabbage or broccoli.

"I think we need to be more flexitarian. We need to get used to having a lot more vegetables and much less animal-derived fare on our plates. But in terms of taste, nothing should be absent. Therefore, my vision is that we add something from the animal kingdom that really boosts taste, so that we can make do with very small amounts - but enough to provide flavours that vegetables can't," says Mouritsen. He continues:

"Here, it is obvious to use raw materials from the sea that can be sustainably made the most of. This includes species that are not overfished, species that are wasted as bycatch, or species that are not consumed by humans."

He emphasizes that it should be up to other professionals to determine which species are sustainable to use. While many fish species are overfished and a great deal of fish farming is environmentally harmful, the production of 'blue foods' sourced in marine and other aquatic environments is often far more sustainable than the production of land-based meat and plant protein, which often require large inputs of water and energy.